So Urashima thought to himself: “A fish would do for my dinner just as well as this tortoise,—in fact better. Why should I go and kill the poor thing, and prevent it from enjoying itself for another nine hundred and ninety-nine years? No, no! I won’t be so cruel. I am sure mother wouldn’t like me to.” And with these words, he threw the tortoise back into the sea.

Basil Hall Chamberlain, 1886 retelling of the tale of Urashima Tarō

“Monsters make for disquieting playmates,” in the words of a November 1999 TIME Magazine cover story on the Pokémon phenomenon. “No matter how toylike and frivolous they may appear, monsters, are unnatural and, in the end, deal in unresolved fear.”1 Thus far, we’ve seen Pokémon descendants of mythical creatures embodying fears of fire, of disease and contamination, and of drowning. My main source for the previous post, about the dragon Pokémon Charizard, was literally titled Dragon: Fear and Power.

This is not the whole story, however. My mind goes to the late, great stop-motion animator Ray Harryhausen, who insisted that his characters were not monsters but creatures – not inherently evil, but animals operating on instinct, or under the control of human villains.2 Yes, Harryhausen’s last and most elaborate film Clash of the Titans (1981) features Medusa, the kraken, and a monstrous scorpion, but it also stars the winged horse Pegasus, who exemplifies mythical creatures’ ability to embody our hopes as well as our fears.

If you’re a human being, you’ve dreamed or daydreamed about what it would be like to fly, to soar above mountains and dive down through valleys, to look down at your town and see a toy cityscape.

Yes, Pokémon represent fears to be faced and obstacles to be overcome, but they also represent these profound dreams. In the Pokémon world, trainers can use their creatures to take flight, to dive down to the seabed, to swim across oceans to distant islands, to teleport from city to city.

This post will cover the Pokémon Wartortle, who evolves from Squirtle at level 16 and descends from a mythical creature who embodies a universal human hope, that of a long life.

Turtles’ global range – they inhabit every sea and every continent except Antarctica – makes them a common feature in global mythologies. From Aesop’s slow and steady tortoise3 winning the race against the arrogant hare to the Chinese Black Tortoise, who represents the north and winter, turtles play many mythical roles, some of which are represented by turtle Pokémon.

Squirtle, for instance, is a distant descendant of the kappa, a creature often depicted with a turtle’s shell and beak. The fourth-generation starter Turtwig evolves into Torterra, a creature that clearly evokes the world-bearing turtles of Chinese, Hindu and indigenous American mythologies. The fifth-generation fossil4 Pokémon Tirtouga and Carracosta take after the sea turtle, a central figure in Hawaiian mythology.

Wartortle’s mythical ancestor is the legendarily long-lived turtle minogame, a creature best known for its role in one of Japan’s most famous and oft-retold legends, the tale of the fisherman Urashima Tarō.5

The tale begins with Urashima Tarō saving a young sea turtle from a group of boys intent on torturing it. He takes the turtle back to the sea, releases it, and watches it swim away.

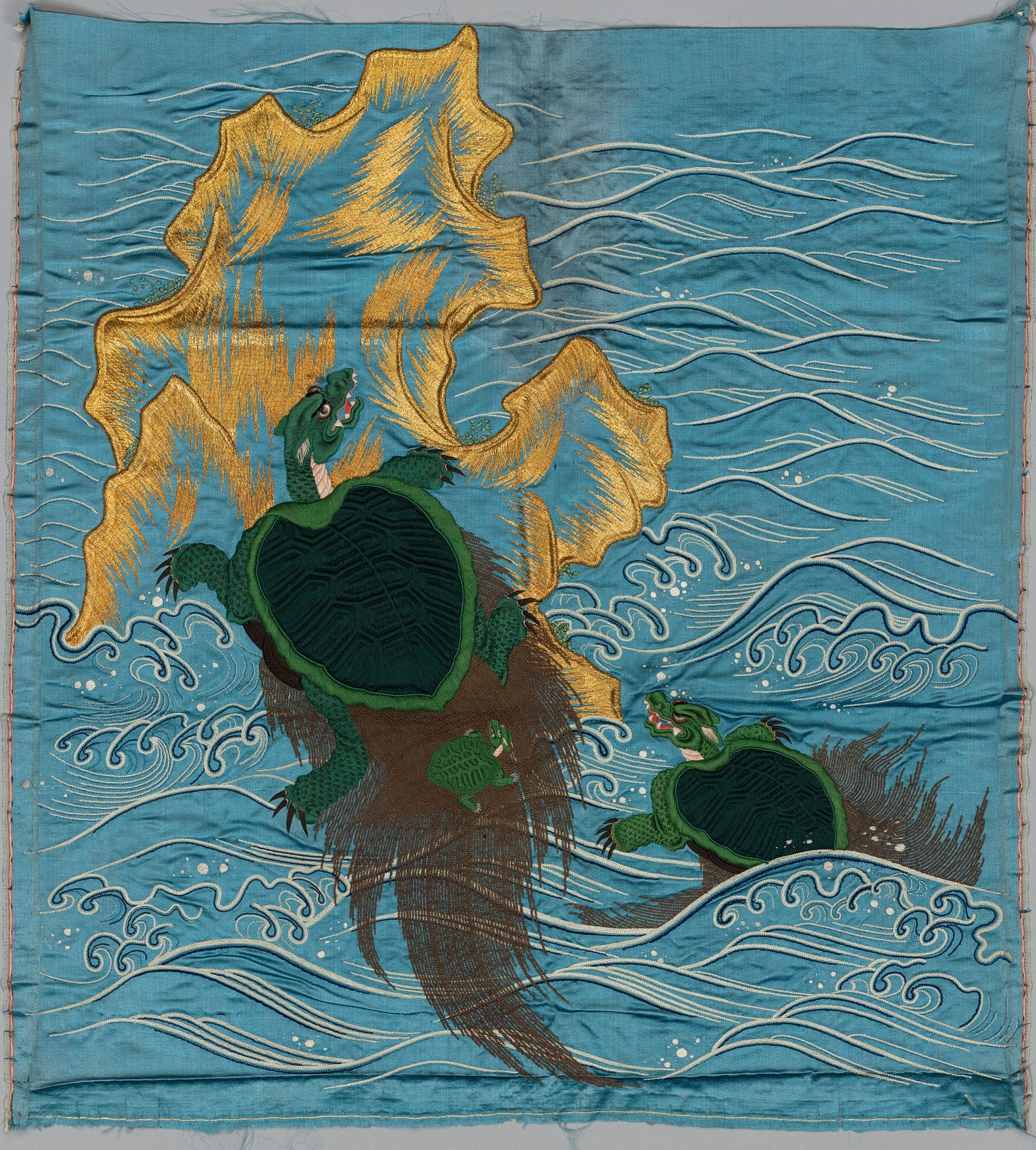

The next day, he is visited by a giant sea turtle, who informs him that the small turtle he saved was actually a princess, the daughter of Ryūjin the Dragon King of the sea, who lives in a coral palace on the ocean floor. In some versions of this story, this royal messenger is merely a very large sea turtle. In others, however, it is the minogame, a turtle that can live a thousand years, with long strands of algae trailing behind it like a hundred tails.

Urashima Tarō rides on the turtle’s back to the undersea palace, where he attends a banquet in his honor and meets – and falls in love – with the princess Otohime in her true form. After three days in the dragon palace, Tarō becomes homesick and asks permission to return home to visit his family. This permission is reluctantly granted and Otohime gives him a parting gift, a jeweled box that will protect him, as long as he never opens it.

Tarō returns home on the back of the minogame to find that his village has completely changed and that no one there recognizes him. Dragon palace time, like Narnian time, flows differently than ours; three hundred years had elapsed during his time on the ocean floor and everyone he ever knew is long dead. Tarō opens the box and dies after instantly aging three hundred years. The box contained, depending on the telling, either his old age or all the time he had spent in the palace.

While this incredible tale – with its echoes of Pandora’s box, voyages to Tír na nÓg in Irish mythology, Rip van Winkle, and modern stories of time travel and time dilation – deserves a post of its own, I will focus on the minogame. Its role in this story about time, aging and transience contributed to its prominence as a symbol of longevity.

The origin of the word is clear enough – a combination of mino, a traditional straw cape, and kame,6 turtle. A turtle with strands of algae and seaweed trailing after it like a cape. This aspect of its appearance, in turn, begins with reality. Algae and moss can grow on turtle’s shells, giving their backs a fuzzy appearance that was embellished into the minogame’s many tails.7 This transformation was likely aided by the similarity between these trailing algae strands and an obvious symbol of a long life, an old man’s long beard.

The choice of a turtle to represent longevity also originates in reality; turtles are the world’s longest living land animals. The second most famous inhabitant of Saint Helena, for instance, is an approximately 192-year-old Seychelles giant tortoise named Jonathan, who has lived on the island since 1882. Several other turtles have lived longer than any human being, including a radiated tortoise named Tu'i Malila (approximately 189 years), a Galápagos tortoise named Harriet (approximately 176 years), and a Greek tortoise named Timothy (160).

Because of all this, the minogame became a symbol of longevity in Japanese culture. Both wedding kimonos and wedding gifts traditionally featured the minogame alongside cranes – another symbol of longevity – as a way to visually wish the newlyweds a long and happy marriage. For the same reason, they became a motif for luxury anniversary gifts.

Visually, Wartortle’s bushy tails reflect the minogame’s trailing strands of algae, perhaps combined, as Bulbapedia suggests, with stylized depictions of ocean waves. (Its winged ears, by contrast, seem to evoke either Wagnerian helmets or the Greek god Hermes’ winged staff and sandals.)

While first generation Pokédex entries cover the creature’s swimming and ability to pull in its head like a real-world turtle, later Pokédexes use language that clearly evoke the minogame and its most common meaning. In the words of the Pokémon Gold Pokédex, for instance, Wartortle “is recognized as a symbol of longevity.” According to the Pokémon Crystal entry, “its long, furry tail is a symbol of longevity, making it quite popular among older people.” From these second-generation games to the current (ninth) generation of Pokémon, Pokédexes repeat or paraphrase this language about Wartortle’s tail and longevity.

Its appearance and these Pokédex entries aside, however, Wartortle is this series’ first example of a mythically inspired Pokémon who fails to truly take advantage of that inspiration.

Charizard, the subject of the previous post, represents an effective Pokémonization of the European dragon. The starting trio of Bulbasaur, Charmander and Squirtle all have powers that in some way reflect their mythical roots: the poison of real-life (and folkloric) frogs, the salamander’s invulnerability to fire, the kappa’s embodiment of water’s dangerous power.

In the case of Wartortle, however, the connection to the minogame does not extend beyond Pokédex entries to actual gameplay.

For one, the choice to turn minogame into an intermediate stage Pokémon is an odd one. How can Wartortle serve as an effective symbol of longevity and old age if it only stays a Wartortle for twenty levels before evolving into an older and larger creature? Blastoise, the final evolved form of Squirtle, would have been the obvious pick for Pokemon’s minogame analogue: the family’s final evolutionary stage, a creature that has grown from childhood to adolescence to full maturity. Pokémon designers, however, went in a different direction for Blastoise, taking inspiration not from the minogame but from the movie monster Gamera.

In battle, Wartortle uses an assortment of physical (Tackle, Bite, Rapid Spin, Skull Bash) and water elemental (Bubble, Water Gun, Hydro Pump) attacks, with no powers related to time and longevity. Imagine a true Pokémon equivalent of the minogame, one that could slow down or manipulate time, or a legendary creature found only in a seabed dungeon.

While a perfectly fine Pokémon in its own right, then, Wartortle represents a missed mythological opportunity. It does, however, also represent something important for this project – that Pokémon’s creators had mythical creatures in mind when designing their menagerie of characters.

Chua-Eoan, Howard, and Tim Larimer. "Beware of the Pokemania." Time, 22 November 1999.

Ray Harryhausen: An Animated Life by Harryhausen and Tony Dalton. Aurum Press, 2010.

In researching this piece, I learned that tortoises are a subset of turtles (class Reptilia, order Testudines.) All tortoises are turtles, but not vice versa.

In a nod to Jurassic Park, Pokémon games regularly feature Pokémon that can only be obtained by finding and reviving fossils.

If you’re a fellow fan of the sui generis writer Lafcadio Hearn (also known as Yakumo Koizumi), you might know his retelling in the essay “The Dream of a Summer Day,” part of the 1895 collection Out of the East.

Wartortle’s original Japanese name is Kameil. If you’re a Dragon Ball fan, you might remember that the turtle hermit Master Roshi lives in Kame House.

In Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan (1894), Lafcadio Hearn writes that “some of the tortoises kept in the sacred tanks of Buddhist temples attain a prodigious age, and certain water-plants attach themselves to the creatures' shells and stream behind them when they walk. The myth of the minogame is supposed to have had its origin in old artistic efforts to represent the appearance of such tortoises with confervae fastened upon their shells.” Merriam-Webster defines confervae, a word with which I was unfamiliar, as “any of various filamentous algae that form scums in still or sluggish fresh water.”

So much rich information in here, even for someone like me who only knows Pokemon peripherally.

Love how you reach really deep into all kinds of folklore to pull these kind of insights.

Honestly, after hearing you talk about it, yeah, Wartortle seems a bit like a missed opportunity. Even if they couldn't mess with Blastoise's design that much, they had another opportunity to bring back Wartortle's design motifs with Mega Blastoise.