#006: Charizard

The Dragon and His Wrath

But the land of Merlin and Arthur was better than these, and best of all the nameless North of Sigurd of the Völsungs, and the prince of all dragons. Such lands were pre-eminently desirable. I never imagined that the dragon was of the same order as the horse. And that was not solely because I saw horses daily, but never even the footprint of a worm. The dragon had the trade-mark Of Faërie written plain upon him. In whatever world he had his being it was an Other-world. Fantasy, the making or glimpsing of Other-worlds, was the heart of the desire of Faërie. I desired dragons with a profound desire.

J.R.R. Tolkien, “On Fairy-Stories”

Charizard brings us back to the Borges quote that gave this newsletter its name: to the dragon, mysterious as the universe itself, appearing again and again in the human imagination. I will not attempt to explain the universe or solve the mystery of the dragon here. As Martin Arnold writes in the introduction to The Dragon: Fear and Power, “dragons as depicted across world myth and legend are so varied in their behaviors and appearances, let alone their cultural significances, that any attempt to provide an all-purpose description of them is simply impossible.”

Instead, this essay will give a brief history of the European dragon, beginning in the ancient world and ending with the Pokémon Charizard, its direct descendant.1

Where did the dragon come from? There is of course no one answer. In “On Fairy-Stories,” Tolkien uses the metaphor of a bubbling cauldron, containing ingredients added at different times and places, to describe the complex history of folklore. Whatever now-shadowy historical figure inspired King Arthur, he writes, “was boiled for a long time, together with many older figures and devices, of mythology and Faerie, and even some other stray bones of history (such as Alfred's defense against the Danes) until he emerged as a King of Faerie.”

A recipe for what became the familiar, fire-breathing medieval dragon would include at least the following ingredients:

1. A possible genetic inheritance from our distant ancestors. In The Dragons of Eden: Speculations on the Evolution of Human Intelligence, Carl Sagan suggests that the dragon could be an ancestral memory of our “ancient enemy,” the snake. Building on Sagan, anthropologist David E. Jones argues for dragons as a combination and amplification of three key ancestral predators: snakes, big cats and birds of prey. He calls this the “snake/raptor/big cat complex” in his book An Instinct for Dragons and connects the dragon’s fiery breath to the hot breath of big cats.

2. Fossils of dinosaurs and other prehistoric reptiles. Ancient people presumably shared our fascination with dinosaur skeletons, our drive to imaginatively reconstruct them, add flesh and scales, and visualize them as living creatures.2

3. Observations and especially embellished travelers' tales of real reptiles. The medieval bestiary’s dragon is not Of Faërie but instead a large reptile that lives in India and Ethiopia and hunts elephants; images and descriptions of the prey are only slightly less fanciful than those of the predator. St. George, as discussed below, slew his dragon not in some imaginary land but in modern-day Libya. One can image traveler’s accounts of crocodiles, pythons and spitting cobras growing in the telling as they made their way to Europe.

4. The snake as an ancient symbol of fertility and regeneration: sloughing off its own dead skin and emerging as if reborn. The ouroboros symbol of the snake eating its own tail originated in ancient Egypt, whose pharaohs once wore representations of the snake goddess Wadjet on their crowns. Minoan figurines known as "snake goddesses" hold snakes in each hand; on the mainland, the half-man, half-snake Cecrops was said to have founded Athens. King Arthur himself is the son of Uther Pendragon (“dragon’s head” or “chief dragon” in Welsh.) As with the bear, the snake’s power as a pagan symbol contributed to its demonization in the Christian era.

5. The reptilian monsters of ancient Greek mythology. These creatures, completely lacking Cecrops’ civilized/civilizing qualities, include the gigantic serpent Python, slain by the god Apollo at Delphi, and the multi-headed Hydra slain by Herakles as one of his labors. The hundred-headed Typhon – the father of Cerberus, the chimera, and the sphinx – warred against the Olympian gods until Zeus buried him under Sicily’s Mount Etna, whose eruptions were attributed to his rage.

One particularly influential Greek myth was the story of Perseus, who rescued the princess Andromeda from a sea monster. This archetypal hero-princess-dragon scene – which you might know from either version of Clash of the Titans – provided a template for later dragon legends such as that of Saint George.

6. Monsters in other Mediterranean and Near Eastern mythologies. In Egyptian mythology, for instance, the sun god Ra makes a nightly descent into the underworld, where he slays slay the monstrous serpent known as Apep or Aapef before rising as the dawn. Similarly, the Babylonian god Marduk fights and eventually kills the draconic sea goddess Tiamat; his Hittite counterpart slays the sea dragon Yam.

7. Monsters in pagan Northern European mythologies. Two fearsome serpents inhabit the world of Norse mythology: Níðhöggr, who gnaws at the roots of the world-tree Yggdrasil, and Jörmungandr, the world-serpent who dies fighting (and fatally poisons) Thor during Ragnarök. Beowulf also kills and is fatally poisoned by a dragon in that half-Christian, half-pagan epic poem. The “nameless North of Sigurd of the Völsungs” that so entranced young Tolkien was the world of the Germanic heroic sagas — most famously preserved in the High German epic poem the Niebelungenlied (c.1200) — that inspired both The Lord of the Rings and Richard Wagner’s Ring Cycle. In it, the monomythical hero Siegfried (or Sigurd) slays the dragon Fáfnir, eats its heart and drinks its blood, which gives him magical powers.

8. The dragon standard carried by cohorts of Roman soldiers. This use of the dragon to symbolize the Roman Empire may have contributed to the dragon as a symbol of evil in the Book of Revelations and in Christian Europe after the fall of the western Roman Empire.3

9. Dragons and dragon-like creatures in the Bible, beginning with the serpent in the garden of Eden. The Book of Job describes the sea monster Leviathan as breathing smoke and fire; its mouth became the mouth of Hell itself in medieval Christian art. The Book of Revelation, of course, features the climactic, apocalyptic triumph of the archangel Michael over “that old serpent, called the Devil and Satan,” which John of Patmos describes as seeing in his dream vision as “a great red dragon, having seven heads and ten horns, and seven crowns upon his heads.” For Martin Arnold, the satanic dragon’s long-term influence “cannot be overstated.”

The combination and Christianization of these ingredients created the medieval bestiary dragon, an unambiguously evil creature. A twelfth century English bestiary, for instance, describes every aspect of the dragon as representing the devil, from its size to the crest on its head — a symbol of pride — to its habit of ambushing elephants and strangling them with its tail, which stands for the devil's deceitfulness and ability to entangle humans with "the knots of their sins."4

As with earlier monsters, the medieval dragon became the hero’s ultimate test; Borges calls dragon-slaying “one of the stock exploits of heroes” in The Book of Imaginary Beings. England’s patron St. George is only the most famous of many saints who encountered dragons in their legendary adventures.

The historical St. George came not from England but from the eastern Mediterranean, probably Cappadocia in modern-day Turkey. According to early Christian tradition, he was a 3rd-4th century Roman military commander who refused to renounce his Christian faith during the Great Persecution of the emperor Diocletian, who eventually had him executed. Arnold credits the influence of Greek myth, the Book of Revelation and medieval chivalric romance for the dragon becoming first a symbol of this oppression and then taking on a life of its own. To return to Tolkien’s metaphor, George was boiled together with and seasoned by these myths, especially that of Perseus and Andromeda, and then emerged as a Faërie knight, if not the Faërie knight.

The mythical St. George arrives in Libya to find it plagued by a swamp-dwelling dragon unappeased by the locals’ sacrifices of livestock and, eventually, of their own children. In a clear echo of Andromeda, the desperate Libyan king sends his daughter off to the swamp as a sacrifice to the dragon. St. George rescues her, slays the dragon, baptizes the local population and inspires the local king to build his town’s first church. He then rides off into the sunset — as Arnold writes, “declining any reward for his deed and having instructed the king in the right-minded Christian way to rule over his subjects.” This George still dies a martyr’s death under Diocletian, at least in the earlier tellings of this story, but not before symbolically triumphing over paganism.

History has become archetype, with a global appeal. Arnold lists George’s many patronages in addition to England:

Aragon, Catalonia, Georgia, Lithuania, Ethiopia, Bulgaria, Palestine, Portugal, Brazil, Canada, Romania, Germany, Greece, Malta, Moscow, Istanbul, Genoa and Venice. He has traditionally been venerated by soldiers, farmers, archers and horse-riders and has been seen as a guardian of lepers, plague victims, and those suffering from syphilis.

The flags of England, the United Kingdom, the City of London, Georgia, Barcelona, the Canadian provinces of Alberta, Manitoba and Ontario, and the isles of Guernsey and Sark all incorporate St. George’s red cross into their designs. The United Kingdom awards the George Cross, one of its highest honors, to “those who have displayed the greatest heroism or the most conspicuous courage whilst in extreme danger,” in the words of the Victoria Cross and George Cross Association.

St. George was not the only dragon-slaying saint; I’ve already mentioned the archangel Michael, who slays the dragon Satan in the end times. Raphael painted Saint Margaret of Antioch, who survives being swallowed by a dragon by making the sign of the cross in the belly of the beast, which causes it to explode around her. St. Romanus of Rouen slays a dragon and uses its head as the first gargoyle. St. Donatus kills a dragon by either spitting into its mouth or striking it with a whip.

Perhaps even more relevant for our purposes are the various dragon-taming saints of medieval legend:

Matthew the Apostle, who, according to one decidedly non-canonical legend, tames two formerly violent dragons.

Ammonius the Hermit, who tames two dragons and has them guard his desert hermitage from thieves.

Clement of Metz, who tames a dragon called le Graoully, converts the inhabitants of Metz to Christianity, and becomes the city’s first bishop.5

Martha of Bethany, the sister of Lazarus, who leads a tame dragon – the Tarasque – through the Provençal town of Tarascon and remains its patron saint.

In its own way, as I will discuss later in this post, Pokémon offers a distant echo of these hagiographies.

A combination of factors – the age of exploration filling in blank spaces on the map, the rise of zoology as a science, the exposure of supposed dragon remains as stitched-together frauds – ended belief in dragons as real animals. While there are creatures called dragons in today’s zoology, such as the Komodo dragons of Indonesia, they are no hydra, no Níðhöggr, no Devil.

Extinct to science, dragons lived on in fantasy media. If Joseph Campbell’s archetypal hero has a thousand faces, then the dragon has almost as many, with starring roles in fantasy novels, movies, cartoons, tabletop RPGs and video games.

The European dragon has extended its range far beyond Europe. Godzilla, for instance, takes after it rather than the equally ancient Asian dragon. In his 1954 debut, he first comes ashore on an isolated island whose oldest resident recalls an old legend – a legend, echoing those of Perseus and St. George, about a sea monster named Godzilla who devours the island’s fish supplied unless propitiated by a virgin sacrifice. Named after this legendary character, the enraged, mutated dinosaur rampages through Tokyo with the dragon’s malevolence and an atomic age version of its fiery breath.

Japanese RPGs also abound in dragons, from Dragon Quest/Dragon Warrior (1986) onward. Quite a few of these games feature echoes of the dragon-taming saints, a pop culture thread that Arnold also traces through Game of Thrones’ Daenerys Targaryen, Anne McCaffrey’s Dragonriders of Pern series, and How to Train Your Dragon. In the Fire Emblem Games, for instance, both shapeshifting human-dragon hybrids and mounted wyvern riders fight in player-controlled armies. In RPGs both eastern (Breath of Fire, Drakengard, Final Fantasy, Panzer Dragoon) and western (The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, World of Warcraft), dragon-taming protagonists are a common sight, which of course brings us to Pokémon and to Charizard.

Charizard has stood out from its fellow Pokémon since the very first games, Pokémon Red and Green, which feature Charizard and Venusaur on their respective boxes; it was, in other words, the very first Pokémon seen by many players.

It remained the mascot of Pokémon Red Version (and its Game Boy Advance remake) in the rest of the world, appearing on millions of game boxes and game cartridges in addition to a draconic horde of plastic figurines, plush toys, t-shirts, and other licensed merchandise.

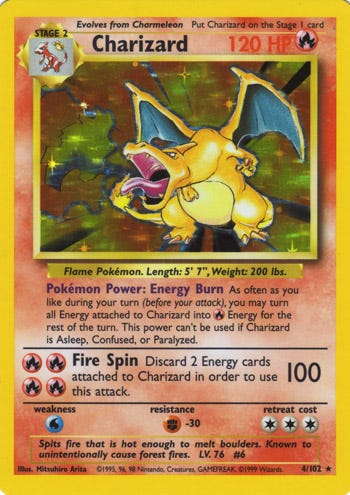

For my fellow millennials, a mention of Charizard probably conjures up a mental image of the holographic Base Set Charizard, the single most sought-after Pokémon card during the height of Pokémania. Even now, a mint condition first edition card can sell for upwards of $400,000; Beckett values pristine copies at around $1 million.

Why is Charizard the most notorious Pokémon card? Because it’s Pokémon’s version of the quintessential mythical creature. The choice of Charizard as a game mascot must have contributed to the franchise’s success, as a dragon on a game box instantly and nonverbally communicates “fantasy adventure” to audiences in any culture.

Like its earlier form, Charmander, Charizard does represent a diminution of a once-overwhelming mythological archetype. It has lost the medieval dragon’s pagan and Satanic overtones, and neither hoards gold nor menaces young princesses. Nonetheless, it retains enough of the old dragon to make it a superstar among Pokémon.

Charizard’s Pokédex entries and trading card flavor text emphasize its sheer capacity for destruction. “Its fiery breath reaches incredible temperatures,” in the words of the Pokémon Stadium Pokédex; this breath “can quickly melt glaciers weighing 10,000 tons.” According to the Red and Blue Pokédex, it “spits fire that is hot enough to melt boulders” and is “known to cause forest fires unintentionally.” Destruction is very intentional in the words of the Team Rocket Set’s Dark Charizard card: “Seemingly possessed, it spews fire like a volcano, trying to burn all it sees.”

Its attacks include Rage, Slash, Flamethrower and Fire Spin in Red and Blue with the addition of Wing Attack, Dragon Rage and Blast Burn in the Game Boy Advanced remakes. Dark Charizard attacks with Continuous Fireball, while Blaine’s Charizard unleashes Roaring Flames and Flame Jet. And, of course, the Base Set Charizard dealt 100 points of damage with Fire Spin, the most powerful Trading Card Game attack of its era.

In the Pokémon anime, Ash’s shy young Charmander evolves into a surly Charmeleon and then into a defiant Charizard who refuses to obey Ash’s orders. As with quite a few anime plot points, this is a dramatization of gameplay that also evokes something more archetypal. In the Game Boy games, a high-level Pokémon acquired in a trade will disobey the player’s commands in battle and sometimes refuse to attack at all. Thus Ash, the anime equivalent of the game protagonist, loses battles against Cinnabar Island gym leader Blaine and league rival Ritchie due to this disobedience.

Seen from a different angle, however, Ash’s struggles to fully tame his Charizard are a literalized metaphor for his personal growth. In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell writes that “the mythological hero is the champion not of things become but of things becoming; the dragon to be slain by him is precisely the monster of the status quo.” The dragon is the roadblock on the road to self-actualization or, to return again to Satoshi Tajiri, an external manifestation of the inner monster, the inner doubt, the inner fear.

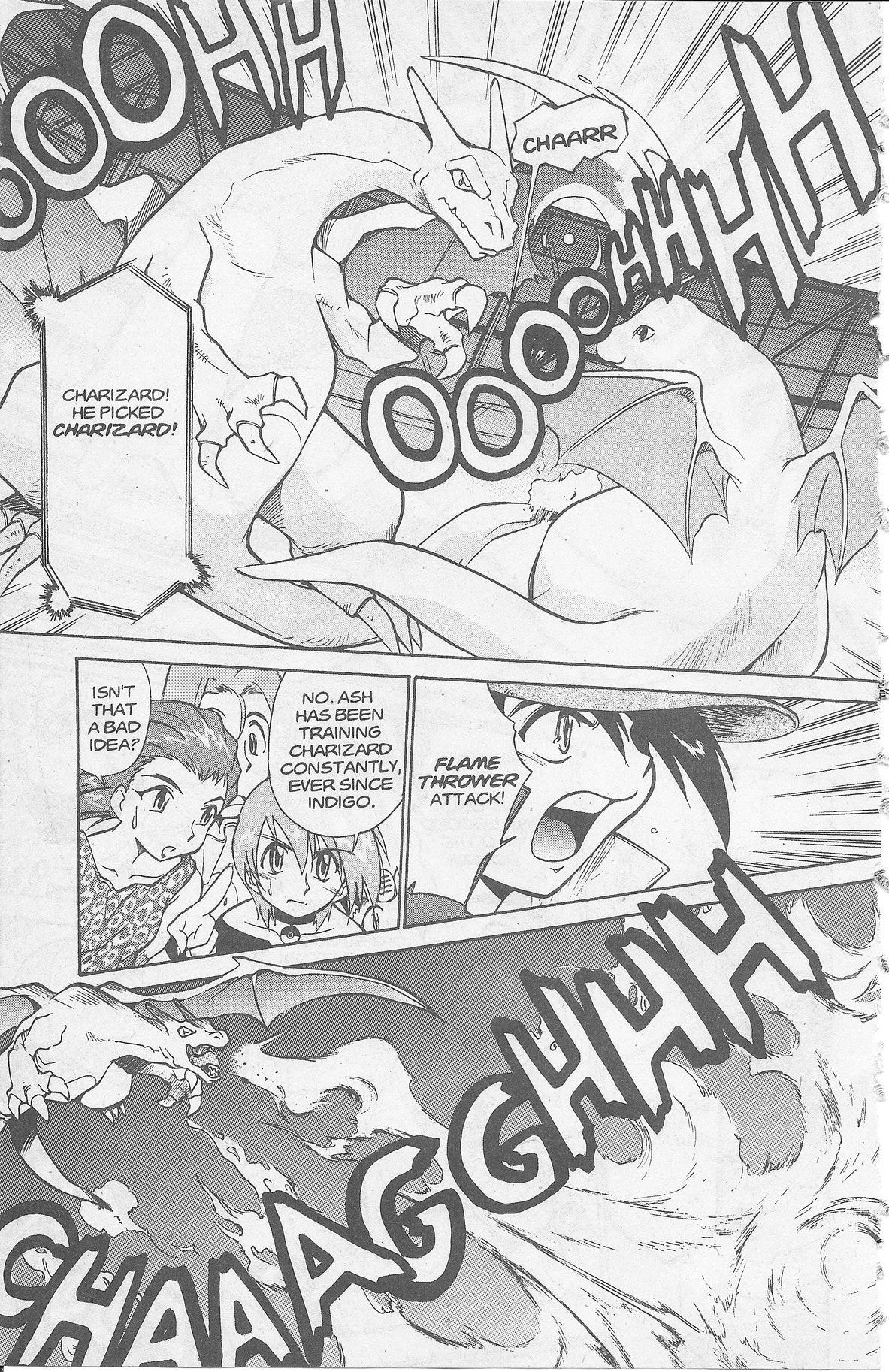

This dragon-taming as coming of age theme is perhaps best seen in The Electric Tale of Pikachu, Toshihiro Ono’s loose manga adaptation of the anime. In the manga’s 12th chapter, Ash enters an important Pokémon tournament, which he hopes to win with his “secret weapon:” a Charizard he painstakingly raised from Charmander childhood. His friends Brock and Misty both express misgivings, with Misty observing that even professionals have a tough time controlling a Charizard.

After winning his first match, Ash faces off against his doppelganger Ritchie in the second round. Down to his last Pokémon, Ash sends out his Charizard against Ritchie’s Charizard ‘Charley.’ Ash’s Charizard becomes completely uncontrollable during the battle, which — combined with the plot contrivance of Ritchie’s malfunctioning Pokéball — forces Ash to forfeit rather than risk serious injury or even death to his opponent’s Pokémon. Afterwards, Misty and Brock interrupt Ash’s ensuing crisis of confidence to give him emotional support, with the latter telling him to never give up.

He doesn’t. As seen above, he enters another tournament in the manga’s final chapter after extensively training his Charizard and gaining its trust. In the finals, Ash triumphs over his opponent, with Charizard playing a major role in his victory.6 He has both successfully tamed his dragon and defeated an opposing dragon;7 he has, in his own childish way, followed in the footsteps of the mythic heroes and dragon-taming saints.

Unlike the anime, which lasted for well over 1,000 episodes with Ash as a perpetual novice who never attains the status of Pokémon Master, Ono’s manga has a beginning, middle and end: an actual coming of age story, ein Bildungsroman that ends with a more mature, more confident Ash as the result of his journey. To quote Brock after that last battle, “you’re all grown up, Ash.” He has tamed his own dragon and vanquished another, and by doing so he has tamed the inner monsters of doubt and fear.

Because the dragon, in addition to its many other meanings, represents the status quo, the obstacle, the limitation to be overcome. In the Greek myths of heroes slaying monsters, in the medieval legends of saints, and, yes, even in the world of Pokémon.

If you’re interested, I’ve written two posts on this theme on my other Substack.

Senter, Phil, Uta Mattox, and Eid E. Haddad. "Snake to Monster: Conrad Gessner's Schlangenbuch and the Evolution of the Dragon in the Literature of Natural History." Journal of Folklore Research, vol. 53, no. 1, 2016, pp. 67-124.

White, T.H. The Book of Beasts: Being a Translation from a Latin Bestiary of the 12th Century. 1954. Dover, 2010.

I had the joy of seeing its wooden effigy in the cathedral crypt when I visited.

Of course, Pikachu wins the battle.

As seen in Ono’s illustration, this match offers a duel between the western dragon (Charizard) and the eastern dragon (Dragonite.)

Another excellent post. Loved how you went through the mythos surrounding dragons and it's so interesting to see variations of the same theme over and over. Time really is a flat circle lol

Also, it's a little funny that Charizard isn't really classified as a "Dragon" type in the games and is instead "Fire" and "Flying" when it's arguably the most dragon looking Pokémon in Gen 1. Dunno whether it's because of a balance issue given how OP dragon types were, or whether it's due to it being called "Lizardon" in Japanese, a.k.a more closer to a fire lizard than a dragon.

Doesn't matter 'cause Charizard will always be a dragon for me.

This is so interesting! I appreciate the history breakdown and the research you put into these.