That a Salamander is able to live in flames, to endure and put out fire, is an assertion, not only of great antiquity, but confirmed by frequent, and not contemptible testimony.

Sir Thomas Browne, Pseudodoxia Epidemica (1646)

The previous post on Bulbasaur tied multiple threads together: the role played by starter Pokémon in the Pokémon hero’s journey; Bulbasaur’s roots (pun intended) in mythical plant-animal hybrids and in mythical hybridity more generally; Bulbasaur’s powers as echoes of European and Chinese toad folklore.

This post, on the other hand, will follow just one thread, the history of the mythical salamander. While Charmander’s original Japanese name, Hitokage, means “fire lizard,” all of the creature’s western names refer to the salamander. It is also Charmander in Spanish and Italian, Glumanda (IE “glow” or “ember” + salamander) in German and Salameche (salamander + “wick”) in French.

In his autobiography, the French filmmaker Jean Renoir reflects on a childhood dream inspired by a lizard that lived in his family’s garden.1 “Multiplied a hundred times,” he writes, “this innocent little reptile became a very presentable crocodile in my dreams.”2 In the same way, the not entirely innocent little salamander became a very presentable dragon.

How did the real-life salamander, presumably as vulnerable to fire as any other animal, become a mythical fire elemental?3 An invulnerability to fire is the salient fact about the legendary salamander, the only aspect of it that has survived in the popular imagination.

Sir Thomas Browne, who provides this post’s epigraph, proposes one explanation, that the amphibian’s cold temperature and moist skin could potentially extinguish a weak ember. Another possible explanation is the burning sensation caused by the poison secreted by salamanders.4 A third, offered by T.H. White in a footnote to his bestiary translation, is salamanders’ tendency to hibernate in and on logs, which would lead to a dramatic appearance when these logs were thrown onto the fire.5

Using this (rather meagre) raw material, ancient mythmakers built a mythical creature that has survived, in one form or another, for 2,500 years. Its invulnerability to fire is both its oldest and longest lasting aspect. Aristotle himself described the salamander as a creature that lives in fire the way that other animals live in the earth, underwater, or in the sky. According to the Roman military leader and polymath Pliny the Elder, the salamander’s invulnerability comes from its extremely cold body, which extinguishes fires on contact. The Roman writer Claudius Aelianus (c.175-235) describes salamanders as not just able to passively extinguish fires with their cold bodies but as active firefighters who interrupt blacksmiths by extinguishing their fires. Saint Augustine himself referenced the creature’s invulnerability to fire.6

One major ingredient of this myth and of its longevity has to be the danger and fascination of fire itself in a premodern, pre-electrical world. Fire, that world’s only controllable source of light and heat, must have had a numinous power far removed from the cozy, crackling, contained, unthreatening fire’s place in our modern imaginations. In Greek mythology, civilization begins with the titan Prometheus stealing the fire of heaven and giving this gift to humanity; the theft of fire is a common mythological motif across cultures on multiple continents, which speaks to fire’s power as a symbol of human agency and ingenuity.

Fire was of course also an incredible danger in a world of wooden and wattle-and-daub buildings, centuries before modern building codes, flame retardant materials, or high-pressure hoses. The terrible fire that engulfed Notre-Dame de Paris in 2019 was a regular occurrence in medieval and early modern Europe.

London’s old, gothic St. Paul’s Cathedral burned down in the Great Fire of 1666, as did the predecessors of today’s Southwark Cathedral, Hereford Cathedral, Canterbury Cathedral, Newcastle Cathedral and York Minster in earlier conflagrations, to say nothing of countless smaller churches, homes, farms, workshops and other buildings. In this context, the idea of a creature able to walk through fire unscathed would have had an incredible imaginative appeal.

All real-life salamander species are poisonous; some secrete the same dangerous and potentially fatal neurotoxin as pufferfish and blue-ringed octopi. While the salamander’s invulnerability to fire defined its transition from real animal to mythical creature, classical authors often focused more on embellishing its real-life poison into something of truly mythical proportions.

The second century (BC) Greek physician and poet Nicander of Colophon mentions Salamanders in his poems Theriaka, on venomous animals, and Alexipharmaka, on antidotes for poisons.7 He calls the creature both “a treacherous beast, ever hateful” and “the sorceress’s lizard.”8 (Nicander’s cure for salamander poisoning? Honey or boiled mountain tortoise.)

According to Pliny the Elder, the salamander is the world’s most poisonous animal. A salamander climbing a tree, for instance, would render the tree’s fruit and even its bark fatally poisonous. Drawing on Pliny, the bishop, scholar and saint Isidore of Seville (c.560-636) codified the legendary salamander, repeating Pliny’s anecdote about salamanders and adding a sentence about salamanders poisoning well water. Isidore’s paragraph-long description of the creature provided the basis for later medieval bestiary descriptions; the 12th century bestiary later translated by T.H. White describes the creature by reproducing Isidore’s text almost word for word. In the words of a modern translation,

The salamander [salamandra] is so named because it prevails against fire. Of all the venomous creatures its force is the greatest; the others kill people one at a time, but the salamander can slay many people at once – for if it should creep in among the trees, it injects its venom into all the fruit, and so it kills whoever eats the fruit. Again, if it falls into a well, the force of its venom kills whoever drinks from it. This animal fights back against fire; it alone of all the animals will extinguish fire, for it can live in the midst of flames without feeling pain or being consumed – not only because it is not burned but also because it extinguishes the fire.

Bestiary artists drew several different kinds of salamanders, some closer to the real animal than others. Possibly the least true-to-life salamander comes from a 13th century French bestiary now at the Getty Center; this salamander is a large, dark gray dog with multicolored wings, panting with its tongue out as it stands in the middle of a fire At least two other French bestiaries (the 13th century Bestiaire of Guillaume le Clerc and a late 13th or early 14th century Bestiaire d'amour) depict the salamander as a bird in a possible conflation of the salamander and phoenix myths. A 14th century Flemish bestiary’s salamander has a mint-green, arrowhead-shaped head with pointed ears and a catlike face.

Some bestiary salamanders are at least recognizably cold-blooded, amphibian or reptilian. Another 13th century French bestiary, currently at Bibliothèque Municipale de Valenciennes, represents the salamander as a two-legged wyvern with a red head and gray body. The Aberdeen Bestiary salamander is a legless snake, as is the Harley Bestiary salamander; the Royal MS 12 and Bestiary of Anne Walsh salamanders are little blue dragons with pointy mammalian ears. Despite its round ears and pipe cleaner legs, the Sloane Bestiary salamander at least has the black and orange coloration of a real-life fire salamander.

This diversity of salamander body types suggests that medieval Europeans had made a clear distinction between the real amphibian, on one hand, and mythical creature, on the other; the latter seems to be no longer tethered to the former in any way. The bestiary text reflects this disconnect through its complete lack of information on the real salamander’s lifecycle, behavior or habitat. The fire salamander (Salamandra salmandra) was and is common across continental Europe, its range stretching from modern-day Portugal to modern-day Ukraine, but the bestiaries show no firsthand observation of the real animal.

Perhaps the strangest outgrowth of salamander folklore occurs in traveler’s tales of “salamander wool,” which could be woven into fireproof clothing, such as that worn by the legendary African king Prester John. Clothes supposedly made of this “wool” were actually made of asbestos fibers, a substance almost as toxic as the legendary salamander’s poison.

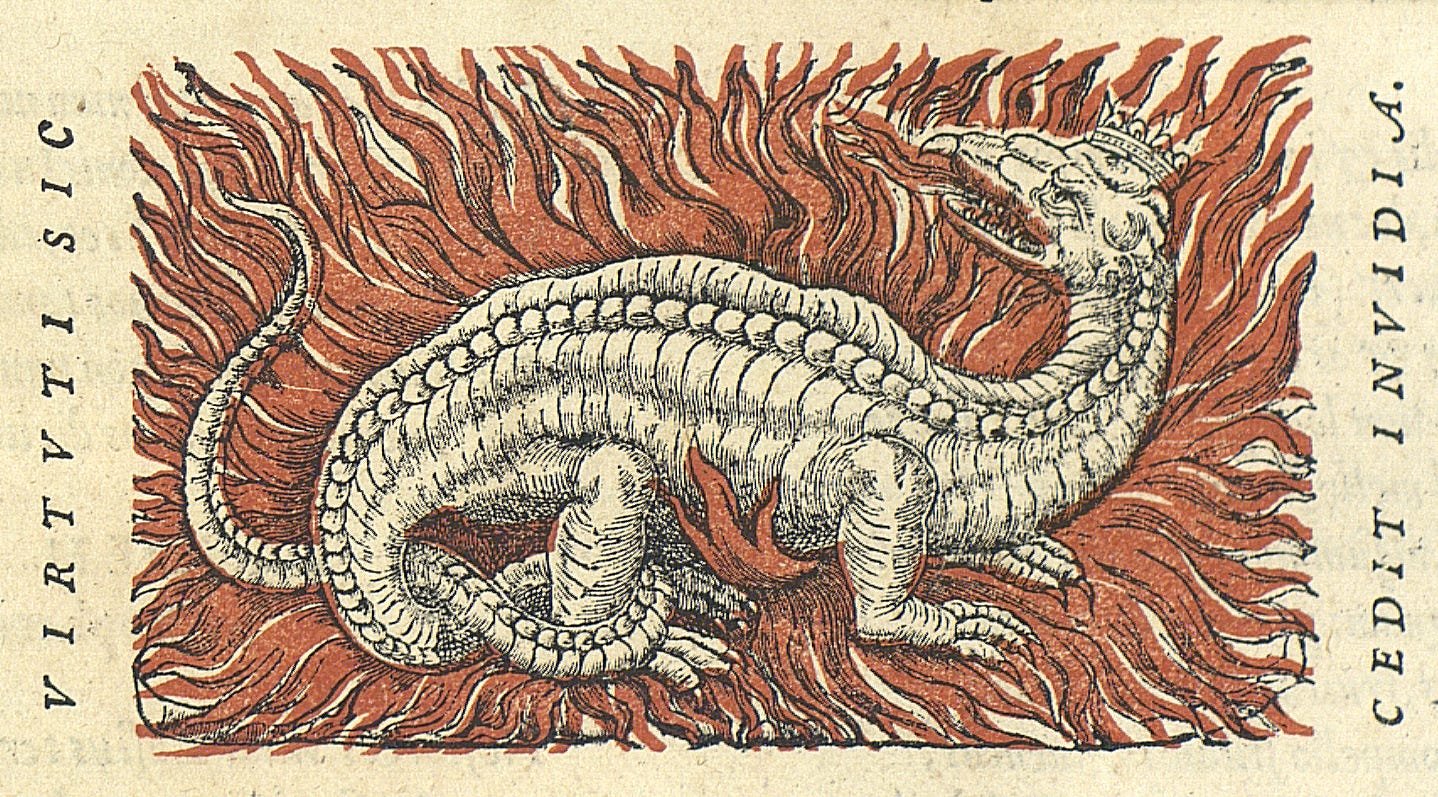

Like many of its fellow bestiary creatures, the salamander escaped the confines of that book to become part of medieval and early modern European visual culture. The French King Francois I (1494-1547) chose the salamander as his personal symbol, which led to a profusion of decorative, crowned salamanders at his chateaux at Chambord and Fontainebleau. For alchemists, the salamander became an obvious symbol of fire, alongside gnomes (earth), nymphs (water) and sylphs (air).9 Both of these developments point to an important shift: from the salamander as a symbol of disease and contamination to one of purity.

Francois chose the salamander to illustrate the pseudo-Latin motto Nutrisco et extinguo (“I nourish and I extinguish”), a simplification of a Latin phrase -- Notrisco al buono, stingo el reo, “I nourish the good (fire) and extinguish the bad)” – that first appeared on a 1504 medallion. This association with a good, purifying fire, which is of course at play in Francois’ likely inspiration, the salamander as alchemical symbol, is the complete opposite of the classical and bestiary salamander, which contaminated trees and water. As if by some alchemical process, the legendary salamander has been transmuted from base, poisonous material into something purer. Into a creature that nourishes the good fire.

Influenced by the “salamander king,” the heraldic salamander became a fairly common feature on French coats of arms, most notably Le Havre and Fontainebleau but also Belleville-en-Beaujolais, Gennes-Val-de-Loire, Le Mesnil-le-Roi, Magny-en-Vexin and Vitry-le-François. The symbolic meaning of these salamanders — Francois’ kingship and, by extension, kingship in general; Francois’ good fire; civic pride; perhaps even francité — takes us a long way away from the poisonous legendary salamander, to say nothing of the poisonous real salamander. These heraldic salamanders also represent an evolution away from the real creature and some of the more fanciful bestiary illustrations, towards a creature very much like a little dragon.

The alchemists’ fire elemental became the dominant form of the legendary salamander in the modern world, a fiery, sometimes fire-breathing close cousin of the dragon. (The classical and bestiary salamander, as we’ve seen, did not breathe fire; it extinguished it.) Players of Dungeons and Dragons, World of Warcraft and other RPGs, for instance, have doubtlessly encountered fire-breathing salamanders on dungeon crawls. Magic: The Gathering players can add no fewer than 17 salamander-related cards to their decks. In Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953), firemen — who start fires instead of stopping them — wear salamander symbols on their uniforms and call their vehicles salamanders.

Like Charmander, these neo-salamanders reflect the legendary creature’s invulnerability to and association with fire rather than its poison. Pokémon’s elemental type system includes Poison; Poison-type Pokémon can use an arsenal of attacks such as Poison Powder, Toxic and Acid. Charmander is a pure Fire-type and can learn none of these attacks, instead attacking its opponents with a combination of literal fire power (Ember, Flamethrower, Fire Spin) and physical normal-type attacks using its claws (Scratch, Slash).

The salamander lost more than its poison en route to the Pokemon world via fantasy RPGs. It lost its overall gravitas, its awe-inspiring character, its association with either contamination (as in ancient and medieval Europe) or purity and kingship (as in early modern Europe.) The legendary salamander’s invulnerability, as we’ve seen, was a defining trait; it was, in Isidore of Seville’s words, the creature that “can live in the midst of flames without feeling pain or being consumed.” Charmander, on the other hand, can be quite vulnerable.

In the Pokémon anime, Ash acquires a Charmander in episode 11, “Charmander – the Stray Pokémon.” This episode begins with Ash and his friends encountering an abandoned Charmander waiting out in the rain for its trainer, who will never return. They rescue it from a potentially fatal rainstorm – Ash’s Pokédex informs him that “a Charmander dies if its flame ever goes out” – and take it to the nearest Pokémon Center, where it survives after a night of intensive care.10 Ash adopts the Pokémon and confronts the original, abusive trainer.

Pliny’s salamander was a toxic creature, “able to destroy whole nations at once;” Ash’s Charmander is a little pet to be taken care of, cute and fragile, a child-friendly version of the old creature with all the sharp edges rounded off. Like all starting Pokémon in the games, it begins as a fragile low-level creature with just a handful of hit points that are easily drained by a few encounters with wild Pidgey or Rattata; the player must constantly monitor its hit points and regularly heal it with Potions or visits to a Pokemon Center.11

For the Base Set trading card, Mitsuhiro Arita illustrates Charmander looking back, surprised, at a tuft of grass it has accidentally lit on fire with its flaming tail, like a young child confused about the effects of its actions. This is not the “treacherous, ever hateful beast” described by Nicander.

Charmander, the child-friendly salamander, represents the endpoint of the legendary salamander’s journey from pandemonium to parade. It lost everything on that journey except for its connection to fire: the relationship with the real-life amphibian, the intense fire-extinguishing coldness, the deadly poison. It does carry that fire, however, along with that fire’s symbolic power. The little TCG Charmander can still start a fire.

In The Dragon: Fear and Power, a cultural history of the dragon, Martin Arnold attributes the popularity of the “nursery dragon” in children’s media to the child’s desire for independence, to the “fantastical conceit” of befriending a dragon as a powerful metaphor for self-actualization. In the introduction to this series, I quoted from an interview with Pokémon co-creator Satoshi Tajiri, who brought up his own sometimes friendly, tamable little monsters as metaphors for taming one’s inner fears and angers.

Charmander the poison-less salamander, the little fire elemental — both incredibly vulnerable to being snuffed out like a candle and potentially powerful and destructive — is the perfect Pokémon to play this role.

Renoir, Jean. Ma Vie et Mes Films. 1974. Flammarion, 2005.

My translation.

“Of the two characters,” Borges writes in The Book of Imaginary Beings, “the best known is the imaginary.”

Hillman, D.C.A. “The Salamander as a Drug in Nicander’s Writings.” Pharmacy in History vol.43 no.2/3, 2001.

White, T.H. The Book of Beasts: Being a Translation from a Latin Bestiary of the 12th Century. 1954. Dover, 2010.

The City of God, book 21, chapter four. In Marcus Dods’ translation: “If, therefore, the salamander lives in fire, as naturalists have recorded, and if certain famous mountains of Sicily have been continually on fire from the remotest antiquity until now, and yet remain entire, these are sufficiently convincing examples that everything which burns is not consumed.”

Wallace, Ella Faye. The Sorcerer’s Pharmacy. PhD dissertation. Rutgers University, 2018.

Wallace’s translation.

Borges, The Book of Imaginary Beings. “No one any longer believes in sylphs,” he writes, “but the word is used as a trivial compliment applied to a slender young woman.” The word is also used in Pokémon. In the Pokémon world, Silph Co. is the company that manufactures Poké Balls and the Silph Scope, which lets the user see ghosts.

This is another direct contradiction of classical salamander folklore; Pliny, perhaps thinking of the real amphibian, writes that “salamander, an animal like a lizard in shape, and with a body starred all over, never comes out except during heavy showers, and disappears the moment it becomes fine.” Charmander, at least the anime version, could apparently not survive such behavior.

The anime Charmander’s vulnerability is a good dramatization of this aspect of the Pokémon games.

Another excellent installment in the series—thank you!

There's also a cultural history of the dragon!? I must get me to the library, having just finished the book about bears which you mentioned in your introductory article.

Your writing is absolutely compelling—thought-provoking, insightful, and deeply engaging. Every piece you publish feels like a chapter in a larger story that deserves to be told in book form. You have a unique voice that needs to reach an even wider audience. Have you ever considered turning your work into a book? I have no doubt it would be an incredible read!