Lady Macbeth: Bear welcome in your eye,

Your hand, your tongue. Look like th’innocent flower,

But be the serpent under ’t.

Macbeth, Act I scene 5

As I research and write these posts, another important reason for Pokémon’s global success occurs to me. This newsletter of course focuses on Pokémon descended from mythical creatures with incredible powers, often rooted in a specific culture. The European dragon, the kappa, the mandrake,1 the baku, the Asian dragon.

Another, possibly larger group of Pokémon take after not mythical creatures but mythologized animals, animals with an archetypal culture status. In many cases, including multiple Pokémon already covered on Necessary Monsters, these animals inhabit wide geographic ranges and play roles in several cultures and mythologies: the toad, the turtle, the butterfly, the sparrow, the mouse.2

Thus, for players – or television viewers, or manga readers, or card collectors – in most countries, the world of Pokémon presents not just a collection of fantastical creatures but a recognizable ecosystem, one inhabited by personally and culturally resonant creatures.

Yes, this is a world where dragons breathe fire and psychic creatures manipulate reality with their mental powers, but it’s also one where bees swarm, butterflies emerge from cocoons, small mammals burrow underground and bats navigate through darkness using echolocation.

This brings us to Ekans and Arbok, Pokémon’s first versions of one of the world’s most universally archetypal creatures, the snake. In the words of anthropologist Roy Willis, “no other animal is so rich in meaning for the whole human species.”3 Even a high-level summary of serpent symbolism would cover a lot of ground: from the half-human, half-serpent Athenian culture hero King Cecrops to the god Apollo slaying the gigantic Python at Delphi; from the serpent in the garden of Eden to Jesus Christ exhorting the apostles to be wise as serpents and innocent as doves; from the ouroboros to calling someone a snake in the grass.

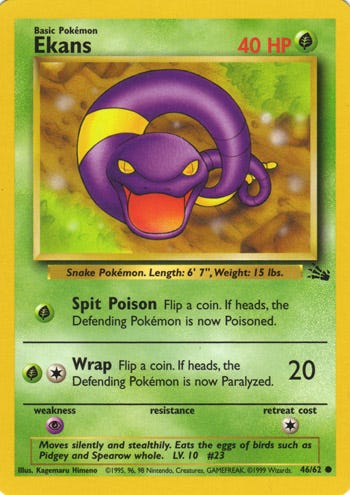

Pure poison types, Ekans and Arbok both clearly take after venomous snakes: rattlesnakes for the former and cobras for the latter. Their most prominent role in the Pokémon universe? The signature Pokémon of Team Rocket4 agent Jessie,5 who along with her partner James and pseudo-partner Meowth is defeated by our heroes in almost every anime episode. (“Team Rocket is blasting off again!”)

Jessie and James’ use of poison-type Pokémon – James uses Koffing, an oddly likeable hybrid of a bomb or naval mine and a cloud of toxic gas – echoes the original Game Boy games, where various Team Rocket agents frequently use poison-type Pokémon including Ekans and Koffing. This association between snakes and villain is archetypal; if you call another human being a snake, you are not complimenting that person.

Because snakes, as previously mentioned, offer an unmanageable profusion of symbolism and mythical resonance, this post will focus on a single attack with mythical echoes.

In a traditional Japanese role-playing game or JRPG, the player has a limited choice of party members; these characters often embody familiar, Dungeons & Dragons-derived archetypes such as the physical fighter, the heavily armored knight, the spellcasting wizard, the healer and the rogue. Final Fantasy VI (1994) was and is praised as a marvel of game design for offering new fewer than fourteen playable characters, each with their own unique fighting style.

Pokémon Red and Blue (1996), released just two years later, allows the player to fill their six party slots with no fewer than 151 creatures. Developers Game Freak used several different strategies to ensure that each Pokémon plays a little bit differently than its 150 comrades.

The most obvious strategy is Pokémon’s elemental type system, which affects gameplay in multiple ways:

Different types6 have different arsenals of attacks. Fire-type Pokémon, for example, tend to attack with direct, damage-dealing moves, while grass-type Pokémon often use moves with indirect effects, such as slowly draining the opponent’s health (Leetch Seed), paralyzing the opponent (Stun Spore), sending the opponent to sleep (Sleep Powder) or increasing the player’s Special/Special Attack stat (Growth).

Elemental strengths and weaknesses based on Pokémon’s complicated, rock-paper-scissors-esque system of type advantages. Water-type Pokémon, for instance, are strong against fire-, ground- and rock-types and weak against grass- and electric-types.

Different types tend to have different distributions of stats (Attack, Defense, Special, Speed.) Electric Pokémon tend to be fast, for instance, while rock-types have high defense.

A few elemental moves have effects outside of battle. Flying-type Pokémon, for instance, can learn the appropriately named Fly, which allows them to quickly fly the player between cities. Water-type Pokémon can learn Surf, which allows the player to swim across various bodies of water.7

Within these elemental categories, Game Freak differentiates Pokémon through their specific movesets and through a strategy they’ve used since the very first games: signature moves, moves that can only be learned by a single Pokémon family. Only Rattata and Raticate, for instance, can learn the damaging dental moves Hyper Fang and Super Fang; only the bivalves Shellder and Cloyster can learn Clamp; only Magikarp, whose gimmick is being a weak Pokémon who evolves into a powerful dragon, can learn the useless attack Splash.

Ekans and Arbok are the only first generation Pokémon to learn Glare. Pokémon Stadium describes this attack in the following words: “The target is transfixed with terrifying sharp eyes. The target is frightened into paralysis.”

The idea of a snakelike creature with a paralyzing glance likely brought one of two enduring mythological characters to mind. First, it could have been Medusa, the snaked-haired gorgon with a petrifying gaze who remains one of the most iconic Greek mythical creatures. An unforgettable character, Medusa is too rich in symbolism, too closely intertwined with other Greek myths and too prolific across millennia of the visual arts — from archaic Greek temple pediments to Ray Harryhausen stop-motion and video games — to be done justice in this post. Especially consider that her Glare is her only major influence on these decidedly non-anthropomorphic snakes. (One other possible nod: the face-like markings on Arbok’s hood, which bear some resemblance to the glaring faces of archaic Medusas.)

Instead of Medusa, you might have thought of the basilisk, a monster that my generation likely first encountered at the climax of Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets. Before battling the creature, Harry reads a description of it, torn from “a very old library book” by Hermione:

Of the many fearsome beasts and monsters that roam our land, there is none more curious or more deadly than the Basilisk, known also as the King of Serpents. This snake, which may reach gigantic size and live many hundreds of years, is born from a chicken’s egg, hatched beneath a toad. Its methods of killing are most wondrous, for aside from its deadly and venomous fangs, the Basilisk has a murderous stare, and all who are fixed with the beam of its eye shall suffer instant death.

Much of this description is authentic European mythology. The name, for instance, comes from the Greek basilískos, “little king,” an appropriate name for a creature consistently referred to as the King of Serpents or King of Snakes. The venomous fangs, deadly stare and strange, cross-species life cycle all reflect much older sources.

The earliest description of the basilisk comes from the Greek physician and poet Nicander of Colophon (2nd century BC), a writer who’s already shown up in these series for his account of the legendary salamander. Nicander’s description of the King of Serpents lacks many key aspects of later, iconic basilisk folklore; his creature is relatively small (“three palms’ width in outstretched length”), lacks wings or any other avian characteristics, is not hatched from chicken’s egg by a toad and, most importantly, does not kill with a murderous stare. Instead, its main characteristic is its venom, which is fatal and renders the victim’s body foul and inedible, even for carrion birds.

The Roman polymath Pliny the Elder, who also appeared in the post on Charmander and the salamander, includes the basilisk in his Naturalis historia, describing the danger it poses in terms not dissimilar to his account of the salamander:

It routs all snakes with its hiss, and does not move its body forward in manifold coils like the other snakes but advancing with its middle raised high. It kills bushes not only by its touch but also by its breath, scorches up grass and bursts rocks. Its effect on other animals is disastrous: it is believed that once one was killed with a spear by a man on horseback and the infection rising through the spear killed not only the rider but also the horse.

Like the salamander, the basilisk is so toxic that it spreads that toxicity to anything it touches. Later in his magnum opus, Pliny extends this idea of indirect poisoning to give the creature a very familiar characteristic – “the basilisk, which puts to flight even the very serpents, killing them sometimes by its smell, is said to be fatal to a man if it only looks at him.”

In a previous post, I quoted a passage from Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces describing the world visited by the mythical hero who has successfully left home and crossed the first threshold: a “fateful region of treasure and danger” populated by “strangely fluid and polymorphous beings.” Fluid and polymorphous, in that case, because of the many myths and legends about humans transforming into animals, or vice versa, and because of Pokémon evolution, which would be better described as metamorphosis.

But those two adjectives also describe another key aspect of mythical creatures: their tendency to transform and to merge over time, their gaining and losing of traits with new tellings. I’ve already discussed the dragon, a monster with a complex ancestry in multiple mythologies and religious traditions; the basilisk of the medieval bestiary and Harry Potter results from a similar albeit simpler development. The snake haired Medusa with petrifying eyes was a possible influence,8 as was a much more obscure creature, the catoblepas.

Like many of the bestiary creatures, the basilisk was further codified in Isidore of Seville’s Etymologiae (7th century), a key source for bestiary writers. Isidore’s basilisk is the King of Snakes, capable of killing with its deadly glance and possessing only one weakness: the weasel, the only animal that can kill it. Thus, the bishop and saint notes, “the Creator of nature sets forth nothing without a remedy.”

The 12th century English bestiary translated by T.H. White repeats Isidore’s text – including its religious moral – almost verbatim, while adding an additional paragraph of lore. The basilisk, a desert dweller, can drive unwary travelers mad with hydrophobia or kill them with its hiss.9

The avian aspects of the basilisk legend, as White observes in a footnote, resulted from a later medieval conflation of the basilisk with yet another mythical creature, the cockatrice. The fuzzy boundary between the two creatures – a situation that White calls “endless confusion”, complete with portmanteau names like “basili-coc” – is reflected in the physical diversity of illustrated bestiary basilisks.

While most bestiary basilisks have rooster’s heads, wings, two legs and a long, twisting snake’s tail, many do not fit that description. Some, such as the Bestiaire de Pierre Beauvais basilisk, lack legs. Others, such as the Douai basilisk, have the head of a dragon. Some are pure snakes, legless and wingless, with no avian characteristics. Others are two-legged or four-legged or even six-legged reptiles. A few wear crowns, as befitting a King of Snakes. The bestiary text itself, which describes a six-inch long basilisk, has been almost completely ignored by bestiary artists, the creature has grown into a monster.

It is this bestiary monster – part gorgon, part catoblepas, part cockatrice – that appears in Harry Potter, Dungeons & Dragons and various JRPGs. Its ancestry also probably also includes real-life venomous snakes such as spitting cobras, as White suggests. One imagines travelers’ tales of these snakes garbled and embellished over time and over various tellings into something truly mythological.

In Isidore of Seville’s account, weasels are the basilisk’s nemesis; in real life, mongooses, benefiting from a genetic mutation that render them immune to snake venom, hunt and kill venomous snakes.10 Possibly unfamiliar with the mongoose, which inhabits subequatorial Africa and southern and southeastern Asia, Isidore substituted a similar European animal.

After gunpowder reached Europe, the monstrous serpent with a deadly glance must have seemed like a perfect metaphor for a newly invented, long-range cannon, which remains known as a basilisk. Shakespeare, never one to resist a pun, plays on both meanings of the word in the French Queen’s address to King Henry in the last act of Henry V:

So happy be the issue, brother Ireland,

Of this good day and of this gracious meeting,

As we are now glad to behold your eyes—

Your eyes which hitherto have borne in them

Against the French that met them in their bent

The fatal balls of murdering basilisks.

The venom of such looks, we fairly hope,

Have lost their quality, and that this day

Shall change all griefs and quarrels into love.

Mythical rather than metal basilisks appear a few times in Shakespeare’s plays. In Richard III, for instance, the loathsome Richard attempts to flirt with Lady Anne: “Thine eyes, sweet lady, have infected mine.” Her response? “Would they were basilisks’ to strike thee dead.”

Of course, giving any Pokémon – especially a common, non-evolved, easily-catchable-in-the-early-game Pokémon like Ekans – an instant one-hit KO attack à la Medusa’s petrification or the basilisk’s deadly glance just wouldn’t work. There are a handful of one-hit KO attacks in Pokémon, but a) they can only be learned by high-level, evolved Pokémon and b) they have a significant drawback, very low accuracy rates, which makes using them an all-or-nothing gamble.11

So Glare, Ekans and Arbok’s signature attack, represents a watered-down version, nerfed in the interest of gameplay balance. A malevolent glare that merely paralyzes an opponent for a time rather than killing it. Like a few other Pokémon we’ve seen in this series, these creatures represent tamed, child-friendly versions of a once-threatening monster.

Strangely enough, Pokémon has never featured a true basilisk in its ever-expanding menagerie. This strikes a me as a missed opportunity; I hope to see a basilisk-inspired Pokémon in a future game. A true basilisk with a truly threatening gaze, perhaps encountered only at the end of a long, grueling dungeon crawl. And a powerful weapon in the player’s arsenal once caught.

Upcoming, when I get to the Pokémon Oddish.

Pikachu will be the subject of the next newsletter.

Quoted in Rodríguez Pérez, Diana. 2021. The Meaning of the Snake in the Ancient Greek World. Arts 10: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts10010002

In the Pokémon games, Team Rocket is a gang whose criminal activities include gambling, smuggling rare Pokémon and fossils, and the attempted takeover of a large corporation, Silph Co. In the words of one member, “we're a group dedicated to evil using Pokémon!” While the player character encounters – and defeats – many Rocket agents throughout his adventure, his anime counterpart Ash pretty much only faces the comically inept trio of Jesse, James and Meowth.

Jessie’s Ekans evolves into an Arbok in episode 31, Dig Those Diglett!

There were fifteen elemental types in Pokémon Red and Blue: Bug, Dragon, Electric, Fighting, Fire, Flying, Ghost, Grass, Ground, Ice, Normal, Poison, Psychic, Rock and Water. Dark, Fairy and Steel were added in subsequent games.

A handful of non-water Pokémon can learn Surf.

Krzyszczuk, Lukasz & Morta, Krzysztof. (2023). Basilisk - the History of the Legend. Alea: Estudos Neolatinos. 25. 277-306. 10.1590/1517-106x/202325116.

Hydrophobia is, per the Cambridge Dictionary, “a great fear of drinking and water, often a sign of rabies.”

Red and Blue’s three one-hit KO attacks – Fissure, Horn Drill and Guillotine – have only 30% accuracy.

"In Isidore of Seville’s account, weasels are the basilisk’s nemesis; in real life, mongooses, benefiting from a genetic mutation that render them immune to snake venom, hunt and kill venomous snakes."

Brings to mind a pair of Pokémon from a later generation, Zangoose and Seviper.

Great article as always. I never made the connection between the move Glare and mythical creatures like Medusa or the basilisk before.

Err.

Snakes with merely hypnotic eyes were a trope before Pokemon.