The hero goes forward in his adventure until he comes to the ‘threshold guardian’ at the entrance to the zone of magnified power. Such custodians bound the world in four directions — also up and down — standing for the limits of the hero’s present sphere, or life horizon. Beyond them is darkness, the unknown, and danger; just as beyond the parental watch is danger to the infant and beyond the protection of his society danger to the member of the tribe.

Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces

TVtropes calls Pokémon #16-22 (Pidgey, Pigeotto and Pidgeot; Rattata and Raticate; Spearow and Fearow) Com Mons, an apt description. Resembling real animals and capable of neither breathing fire nor controlling plant life, they serve as extras in the Pokémon world; their relative ordinariness makes the player’s elementally powered starter Pokémon seem even more magical.

Ubiquitous in the early areas of the game and easily caught, they become entry-level members of the player’s Pokémon team, filling empty party slots and serving as cannon fodder before losing their spots to newer, stronger creatures. Unless the player chooses to seriously train and develop them, they go on to spend most of the game inside of the Pokéball computer storage system while other, more fantastical creatures accompany the player on their adventures.

The biggest star among them is probably Ash’s unfailingly loyal Pidgeotto, his third Pokémon in the anime. Always game, it fights in Ash’s gym battles against Brock and Misty —defeating Misty’s Starmie — as well as in bouts with other rival trainers and Team Rocket. As in the Game Boy games, however, Pidgeotto falls out of the spotlight as Ash assembles a more powerful, more well-rounded team. After Ash captures Bulbasaur, Charmander and Squirtle, Pidgeotto is relegated to the role of benchwarmer or utility player. It serves as an aerial scout, sometimes using its sharp talons to pop Team Rocket’s hot air ballon or flapping its powerful wings to disperse poisonous gases.

Instead of the trusty Pidgeotto, however, this post will focus on the Pokémon Spearow and Fearow1, Pokémon that do not belong to a major anime character, or appear frequently throughout the series, or play prominent roles in other Pokémon multimedia.

At first glance, they might seem like poor fits for a newsletter about Pokémon’s mythological roots. Spearow’s Pokédex entries, for instance, seem unexceptional compared to many others, which emphasize their respective Pokémon’s incredible abilities. The Red and Blue Pokédex informs the reader that Spearow “eats bugs in grassy places” and “has to flap its short wings at high speed to stay airborne.” The Yellow and Pokémon Stadium entries both mention its shortcomings: “inept at flying high” in the former and “can’t fly a long distance” in the latter. Nonetheless, the humble Spearow has two points of interest for this project. First, it represents a Pokémon world version of a bird that inhabits folklores throughout our world. Second, it plays a key monomythical role in both the anime and The Electric Tale of Pikachu, that of the threshold guardian, in a way that reflects a possible mythic influence.

Spearow’s English, Japanese, Mandarin Chinese, Cantonese and Korean names all refer to the sparrow, a humble bird with a global wealth of cultural and folkloric associations. (Its original Japanese name is Onisuzume, “demon/ogre sparrow.”)

If you’re anything like me, your mind goes first to Shakespeare, to Hamlet telling Horatio that “there is special providence in the fall of a sparrow.” Hamlet is of course paraphrasing the words of Jesus Christ, who uses the common, seemingly insignificant sparrow as a metaphor for God’s love and care for all His creatures.

Shakespeare refers to sparrows in ten different plays. Like Hamlet, Adam in As You Like It evokes God’s care for even the small sparrow; the sharp-tongued Thersites in Troilus and Cressida refers to the sparrow’s lowliness in a decidedly non-spiritual context, describing Ajax’s brain as “not worth the ninth part of a sparrow,” a bird that can be bought nine for a penny.

These Biblical and Shakespearean sparrows represent one of the sparrow’s most common symbolic meanings: commonness itself. This, in turn, reflects the real bird’s commonness. According to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, the house sparrow (Passer domesticus) is the second most populous wild bird species on the planet, with a range extending across dozens and dozens of countries on every continent except Antarctica.

This global distribution makes the sparrow a regular presence in folklore and symbolic, often as embodiments of the common, the lowly, the unexceptional.

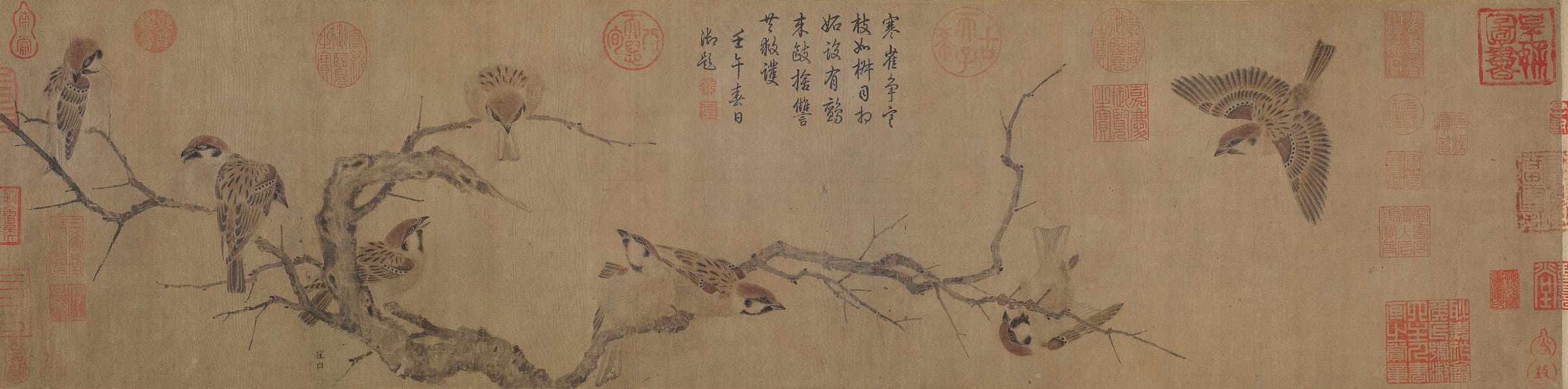

They have long played this role in Chinese poetry and painting. As the scholar Bo Liu writes, ancient Chinese poets and painters contrasted the sparrow, representing the common people, with the larger, more colorful swans and phoenixes, representing the nobility2. Pre-Song Dynasty poetry, in Liu’s words, “detail both its hard life as it suffers from hunger in abandoned cities and empty barns, and its joy at finding unexpected food sources, such as overturned carts carrying grain.”

The Song Dynasty, however, saw a sea change in sparrow symbolism. During this period, the non-aristocratic scholar-painter-poets known in English as the literati painters adopted the sparrow as a symbol of their alienation from political power and desire to live life on their own terms, not society’s. It came to represent both the independence and the hardship of the struggling artist and starred in a new genre of painting: images of sparrows, left out in the cold, living independently among the wintry plants that had long symbolized scholarly virtues.3

In both eastern and western cultures, then, the sparrow represents the common people. It is a humble bird. But also, to mix animal metaphors, an underdog, an avian everyman, a survivor.

Spearow has many of these features. A Com Mon, to use TV Tropes’ label, it is encountered early in the game, at low power levels, and is easy to catch with even an entry-level Poké Ball. While other Pokémon have elemental types that reflect a command of the forces of nature (fire, water, grass, ground, rock, ice) or paranormal powers (psychic, ghost), Spearow is merely normal/flying, merely a bird.

In battle, it attacks using its beak, claws and wings: moves like Peck, Fury Attack, Aerial Ace and Drill Peck. While less fantastical than the elemental or occult powers of more famous Pokémon, these attacks do pack a punch, especially in the early game, when wild Spearow can drain the players’ hit points and/or serve as a strong weapon against rival trainers.

Like the real-life sparrow, Spearow has a wide range of habitats in Pokémon Red and Blue. It appears in no less than nine different locations, including Route 3 (from Pewter City to Mt. Moon), Route 16 (Cycling Road to Celadon City) and Routes 22 and 23 (from Viridian City to Indigo Plateau).4

When first encountered, whether in the games, the anime or Toshihiro Ono’s manga The Electric Tale of Pikachu, Spearow plays an archetypal role in addition to this role of Pokémonified sparrow analogue.

The post on Squirtle mentioned the Campbellian archetype of the threshold guardian, a figure I will describe in more detail here. In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell calls the fourth stage5 of the hero’s journey the Crossing of the First Threshold. As described in this newsletter’s epigraph, this is the moment where the protagonist leaves his or her current situation for the world beyond it.

In Pokémon, as throughout mythology and fiction, this crossing is a literal, physical movement: the game protagonist (and his anime and manga counterparts) leaving his hometown and walking north on Route 1 to Viridian City, Viridian Forest, and Pokémon world’s various haunts of fantastical creatures. On this early stage of the quest, the monomythical protagonist encounters an often frightening adversary who guards this boundary between the familiar and unfamiliar.

Campbell’s primary example of this character is the Greek god Pan, the god of the wild with his namesake pan flute and his satyr’s goat legs with cloven hoofs. Our word panic comes from Pan’s name and this etymology speaks to the specific role played by threshold guardians. These creatures embody the fear of the unknown, of being in an unfamiliar environment outside of one’s comfort zone, of simply being lost.

Ghosts, as I mentioned in a previous post, frequently serve as threshold guardians in various folklores, including contemporary urban legends. They haunt desolate places, abandoned places, places separated from where normal life happens. Like Pan, they condense the general fear of the unknown into a specific character.

Multiple yokai play this role in Japanese folklore, such as the half-human, half-bird called the yamamba, whose name is variously translated into English as “mountain crone,” “mountain witch” or even “malevolent ogress.” As Michael Dylan Foster writes in The Book of Yokai, she is “closely associated with the furtive powers and dangers of the mountains… a space of undomesticated nature into which humans must venture only with care and respect.”6

Japan’s most famous threshold guardian might be the tengu, whose name is sometimes translated into English as “mountain goblin.” Tengu folklore dates back 7th century Japan and remains part of pop culture, with the creatures appearing as mascots of izakaya restaurants, brands of sake and the Generation III Pokémon Nuzleaf and Shiftry. Foster describes them as “one of the best known of all yokai” and identifies folktales of tengu abducting children as an inspiration for Spirited Away (2001).

Like many Japanese myths, tengu originated in China, with the tian guo or heavenly dog. The influential Chinese bestiary known as the Classic of Mountains and Seas describes this creature as resembling a white fox or wildcat and as inhabiting the Yin Mountains of the modern-day Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.

How did this heavenly hound become a bird demon in Japanese mythology, while keeping the same name? It seems like a metamorphosis as strange as in any fairy tale; Foster writes that “it is impossible to unpack the exact process.” Foster does attribute the tengu’s avian characteristics to the influence of the Garuda, a legendary bird in Indian Hindu and Buddhist mythology that Buddhist monks would have brough with them to China and Japan. The Japanese folklorist Kagawa Masanobu attributes this avian translation to the close association — already present in Chinese legend — between the tian guo and celestial phenomena, such as shooting stars, which were interpreted as omens. “In the later Heian Period and into the Middle Ages,” he writes, “the association of the tengu with the skies saw them increasingly depicted as having a birdlike appearance.”

By the 12th century, an originally Buddhist folk belief in the tengu had become part of Japanese culture. In the words of scholar Haruko Wakabayashi, they appear in myths and legends “either as vengeful spirits that seek to disturb the Buddhist law and thereby bring chaos to society, or as enemies of Buddhism that harass the monks and delude the people with their magic tricks.”7 In these stories, an arrogant monk or emperor might be reborn as a mischief-making tengu.

In Edo-era Japan, as Foster writes, tengu “were often evoked as an explanation for mysterious happenings,” such as an unexplained laugh heard in the forest. As with Pan, as with ghosts, the tengu provides an embodiment of strange experiences in an unfamiliar, uncontrolled natural environment.

This period also saw two other important tengu developments. First, tengu developed into two distinct visual forms, the humanoid, long-nosed daitengu or ‘big tengu,’ as represented by the iron mask above, and the more birdlike kotengu or ‘small tengu’ as illustrated by Utagawa. While the Pokémon Nuzleaf and Shiftly clearly take after the daitengu, Spearow bears a certain resemblance to the kotengu, a creature that – at least as drawn by Utagawa – could also be described as a demon sparrow.

Second, the formerly malevolent tengu received, in Kagawa’s words, a “‘promotion’ from a mere yokai to something close to divinity:” to a guardian of mountains and mountain shrines, invoked against fires and other disasters.8 A promotion, in other words, to threshold guardianship, to a protector of wild spaces outside of towns and cities.

Spearow play this role, to some extent, in the original games. When the player first encounters wild Spearow on Route 22 east of Viridian City,9 he or she faces a more dangerous enemy than Route 1’s Pidgey and Rattata: a bird whose sharp beak can put a large dent in their low-level starter Pokémon’s hit points. Spearow’s most memorable performance as a threshold guardian, however, is in the first episode of the Pokémon anime, where it gives Ash a first, child-friendly encounter with nature red in tooth and claw.

In the first episodes of both the Pokémon anime and its manga adaptation The Electric Tale of Pikachu, Ash leaves Pallett Town to chase his dream of becoming a Pokémon master, “the best there ever was.” A true novice who has yet to earn the respect of his only Pokémon, he walks north literally dragging his reluctant, uncooperative Pikachu behind him.

On the road to Viridian City, he encounters several wild Rattata and Pidgey but fails to capture any of them due to Pikachu’s complete lack of cooperation. Frustrated, anime Ash decides to try and capture a Pokémon on his own, throwing a rock at a distant bird that turns out to be a Sparrow straying from its flock. It attacks alongside dozens of its friends and relatives, who swarm like enraged bees.

The whole flock pursues Ash and Pikachu, who flee first on foot and then on a bike commandeered from Misty. The sky dramatically darkens, a storm strikes, and Ash and Pikachu crash the bike, leaving them easy targets for the relentless Spearow. Ash gets up, putting his own body in between his Pokémon and their sharp beaks and talons. Pikachu unleashes a thunderstorm on the Spearow, the clouds clear, and the two (somewhat dazed) new friends walk to Viridian City and further adventures under the arc of a rainbow.

This sequence, as cheesy as it may seem to adult eyes, still works because of its archetypal resonance. Like true threshold guardians, the flock of Spearow are the challenge to be overcome on the threshold between safe, familiar Pallett Town and the fantastical places and creatures beyond it. Ash passes this test, both defeating these adversaries and – more importantly – winning his Pikachu’s respect and trust. He has, as Obi-Wan Kenobi says of Luke Skywalker, taken his first steps into a larger world.

Necessary Monsters readers, would you be interested in a post about Spearow’s evolution Fearow, focusing on its (probably unintentional) connection to the legendary bird of paradise, which was said to live its entire life in flight without ever landing?

Liu, Bo. “Deciphering the Cold Sparrow: Political Criticism in Song Poetry and Painting.” Ars Orientalis, vol.40 (2011).

In Chinese painting and poetry, the trio of pine, plum and bamboo are known as the Three Friends of Winter.

Spearow’s range is not limited to the first generation’s fictional version of Japan’s Kanto region. In Gold and Silver, it appears throughout the Johto region, a fictionalization of the real-world Kansai region, and can be caught on routes 3, 4, 7, 9, 10, 22, 29-33, 42-44 and 46. It can also be encountered in generation four’s Sinnoh region, the Pokémon version of Hokkaido and the Russian coast, and generation seven’s Alola, Pokémon’s Hawaii.

After the Call to Adventure, Refusal of the Call, and Supernatural Aid.

Foster, Michael Dylan. The Book of Yokai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore. University of California Press, 2015.

Wakabayashi, Haruko. “Monks, Sovereigns, and Malign Spirits: Profiles of Tengu in Medieval Japan.” Religion Compass no.7, 2013.

As previously mentioned, the pioneering Japanese folklorist Yanagita Kunio theorized that yokai represent former kami or gods who lost their divine status and were relegated to less lofty, often villainous roles in mythology. Kagawa notes that tengu seem to have moved in the exact opposite direction, “rising from birdlike demons to something close to full-fledged kami at their peak.”

Routes 22 and 23, which lead west from Viridian City to the Indigo Plateau, are an important threshold in the games – between the main game and the endgame, where the player character faces off against the Elite Four and his rival for the league championship (and a place in the hall of fame.) The player can only reach the Indigo Plateau after winning all eight league badges (by defeating all eight gym leaders) and getting through Victory Road, the game’s penultimate dungeon.

I was very curious how you'd handle Spearow and you certainly didn't disappoint. This has been such a fun way to learn about East Asian folklore.

Spearow is so cool. Weird fact: one of my childhood nicknames was Pidgey.