TIME: You liked bugs?

Tajiri: They fascinated me. For one thing, they kind of moved funny. They were odd. Every time I found a new insect, it was mysterious to me. And the more I searched for insects, the more I found. If I put my hand in the river, I would get a crayfish. If there was a stick over a hole, it would create an air bubble and I’d find insects there. I usually took them home.

Pokémon co-creator Satoshi Tajiri, 1999 TIME Magazine interview

Instead of exploring the origin, golden age and pop culture career of a mythical creature, this newsletter about the Caterpie-Metapod-Butterfree and Weedle-Kakuna-Beedrill families will following three different threads.

First, as suggested in this post’s epigraph, Pokémon might not exist save for a young Satoshi Tajiri’s fascination with the insects he found in the woods around his hometown. Therefore, this post will begin by exploring this connection.

Second, the player encounters these insect Pokémon in Viridian Forest, the game’s version of the mythical forest, an archetypal location in heroes’ journeys.

Third, the insect Pokémon’s rapid lifecycles introduce the player to Pokémon evolution, a key gameplay mechanic – and part of the overall Pokémon mythos – that evokes both real-life insects and a universal theme in world mythology.

I will conclude with a look at Butterfree’s most dramatic moment in the anime, a moment that, like Jeff Lebowski’s rug, ties it all together.

Satoshi Tajiri’s childhood love of insects earned him the nickname of Dr. Bug. Born in 1965, Tajiri grew up in then-rural Machida City – a former small town that has since become a Tokyo suburb – and explored local forests, fields and rivers to find and capture insects.1 As he got older, he observed the urbanization process, later recalling that “every year they would cut down trees and the population of insects would decrease. The change was so dramatic. A fishing pond would become an arcade center.”2

That arcade center catalyzed teenaged Satoshi Tajiri’s next fascination, video games. Beginning with homemade, self-published gaming zines, Tajiri pursued a career in video games, connecting with artist and Pokémon co-creator Ken Sugimori and working on Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) games.

He had a flash of inspiration when he first saw the portable Nintendo Game Boy, imagining tiny creatures moving back and forth between two Game Boys connected by a link cable. Along with Sugimori and a handful of other collaborators, he began the development of what eventually became Pokémon, a game that, in his words, represented “everything I did as a kid… rolled into one.” Pokémon would combine his child loves of giant monster movies, science fiction anime and manga, and catching insects, allowing urban Japanese children to virtually experience the joys of bug catching.3

Besides Pallet Town, a fictionalized version of Tajiri’s own hometown, Viridian Forest stands out as the most autobiographical location in in Pokémon Red and Blue’s version of Japan’s Kanto region: a forest where kids hunt for insects with butterfly nets. Besides the player’s rival, these bug catchers are the very first opposing trainers encountered by the player. Are they little homages to young Tajiri exploring the woods around Machida City?

In addition to these autobiographical elements, Viridian Forest has an older, broader relevance.

As a JRPG,4 Pokémon has its equivalents of the genre’s requisite dungeons: the watery caves of the Seafoam Islands, the pitch-black, labyrinthine Rock Tunnel, Lavender Town’s haunted tower. Viridian Forest is the game’s very first dungeon, complete with spooky music. An NPC5 warns the player to “be careful, it’s a natural maze!” While most players who aren’t young children won’t have many problems navigating through this maze, Viridian Forest – both in the games and, as we’ll see, in the anime – represents Pokémon version of the archetypal forest, a prime location for adventure.

The best expression of this idea I’ve ever read comes from Robert MacFarlane’s Romantic travel memoir The Wild Places. Reflecting on the “deepwood,” the forest that once covered Britain before agriculture and industrialization, MacFarlane finds ghostly traces throughout British culture:

we are still haunted by the idea of it. the deepwood flourishes in our architecture, art and above all in our literature. Unnumbered quests and voyages have taken place through and over the deepwood, and fairy tales and dream-plays have been staged in its glades and copses. Woods have been places of inbetweenness, somewhere one might slip from one world to another, or one time to a former.

Shakespeare populating his Athenian forest with fairies and making his forest of Arden a new Eden. Robin Hood and his Merry Men in Sherwood Forest, the Jabberwock lurking in the “tulgey wood,” the entrance to Narnia in the Wood Between the Worlds, Bilbo Baggins and thirteen dwarves trudging through spider-infested Mirkwood: exploring this theme in British literature, to say nothing of any other country, would require its own newsletter. As worlds of their own separate from human civilization, forests are fertile grounds for myth and fantasy.

Viridian Forest has an otherworldly aura in the Pokémon Adventures manga, written by Hidenori Kusaka and illustrated by Mato. In this version of the Pokémon world, people born within the forest are said to have strange powers such as the ability to form wordless, empathetic bonds with Pokémon.

The forest lacks this supernatural quality in other Pokémon media but remains a unique, important place. It is the first in-game dungeon, as previously mentioned, and the setting of several key anime events: Ash capturing his first Pokémon, facing off against another trainer for the first time, and witnessing his first Pokémon evolution; Ash and Misty adjusting to life on the road as traveling Pokémon trainers.

It is, in short, a key step on the Pokémon hero’s journey, a first taste of the fantastical world of adventure beyond the everyday. In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell describes this archetypal place as “fateful region of treasure and danger” inhabited by “strangely fluid and polymorphous beings.” Fluid and polymorphous beings are exactly what the player character — and Ash and Misty, in the anime — encounter in Viridian Forest.

In Toshihiro Ono’s manga The Electric Tale of Pikachu, Ash prepares for his Pokémon license exam by attending a training session. “There is one more aspect of Pokémon that must never be underestimated,” the lecturer tells the students:

Pokémon evolve. It takes terrestrial creatures millions of years to evolve into a different form. Pokémon can transform radically in a very short period of time. This ability to adapt to their environment so rapidly is an incredible achievement! But the source of this ability is steeped in mystery.

While this lecture uses scientific, pseudo-Darwinian language, Pokémon evolution bears a much closer resemblance to mythical metamorphoses than to anything in evolutionary biology. Individual Pokémon evolve, not populations, and instantly, not over many generations.

Indeed, various forms of Pokémon media represent evolution as a sudden, magical event. In the anime, for instance, an evolving Pokémon becomes a glowing, amorphous blob that then transforms into the new creature. In the Game Boy games, a Pokémon’s evolution is an interruption to the normal gameplay — “What? Caterpie is evolving!” — complete with its own theme music.

Players of Pokémon Red and Blue can capture low-level Caterpie and Weedle (levels 3-5) in Viridian Forest. These insects evolve into Metapod and Kakuna, respectively, at level 7, which in turn evolve into Butterfree and Beedrill at level 10. This makes them the fastest evolving Pokémon in the game, and the player’s very first experience with Pokémon evolution unless he or she adopts a very unusual playstyle. They also introduce evolution in the anime; Ash’s Caterpie evolves into a Metapod later that same episode and then into a Butterfree during the very next episode.

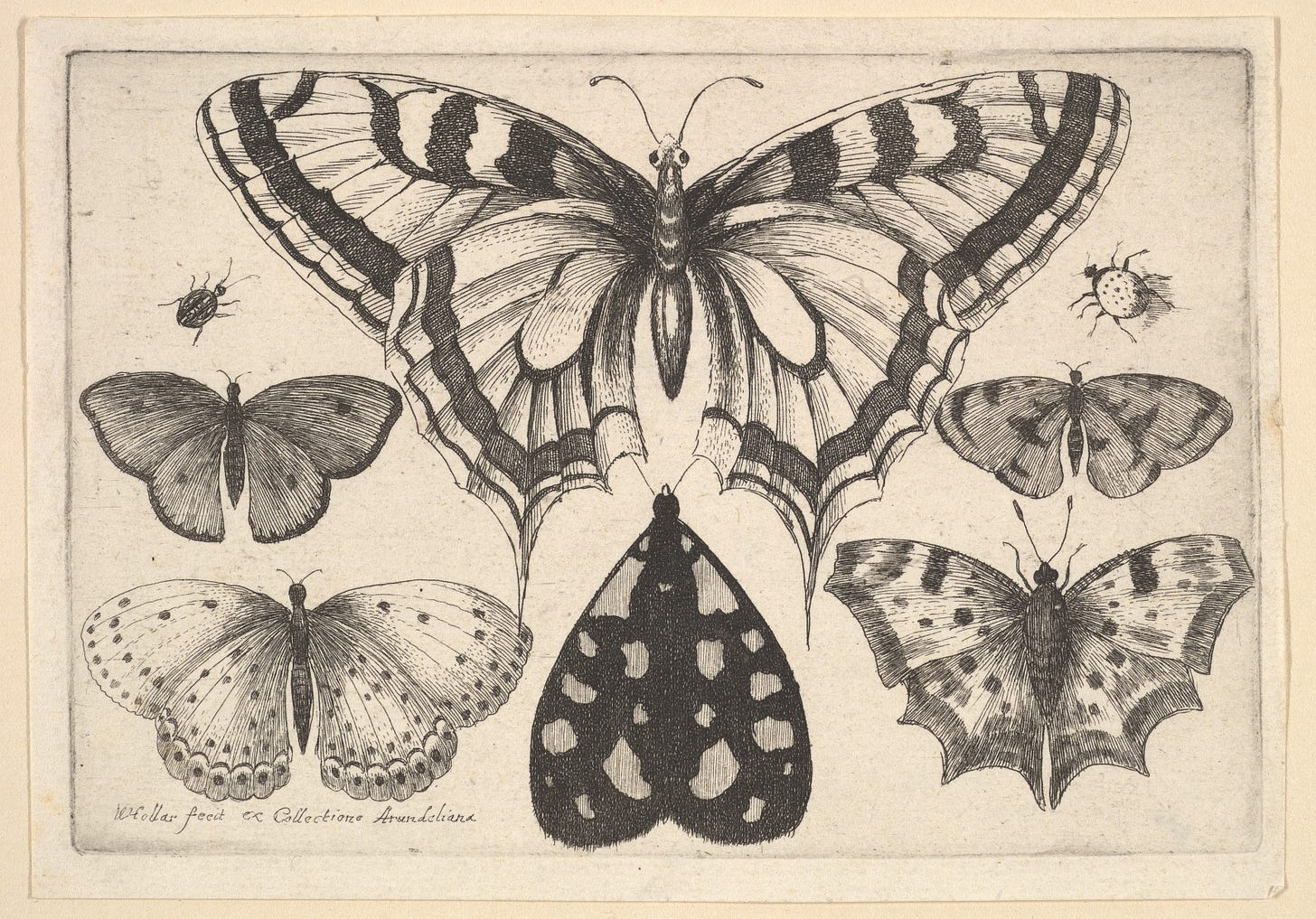

These Pokémon are the perfect introductions to evolution because they evoke reality: the animal kingdom’s most dramatic transformations. In a pre-modern, pre-scientific world, insects’ metamorphic life cycle would have seemed somewhat magical, somewhat supernatural. Baby horses grow into bigger horses, puppies into bigger dogs, but caterpillars completely change their shape and method of locomotion as they grow up, going through an intermediate chrysalis stage with no parallels in the lives of mammals.

Inspired, in some cases, by real-life insect transformations, metamorphoses are a quintessential element of global mythology.

Japanese mythology, for instance, abounds with tales of shapeshifting kitsune and tanuki, in addition to less familiar creatures such as the jorōgumo, a monstrous spider that lures prey by transforming into a beautiful woman.6 Before yokai became the primary term for Japanese mythical creatures, they were commonly known as bakemono, “changing things.”7

In book four of the Odyssey, Menelaos tells Telemachos of his encounter and struggle with Proteus, the prophetic, shape-shifting Old Man of the sea. “The Old Man did not forget the subtlety of his arts,” Menelaos says in Richmond Lattimore’s translation:

First he turned into a great bearded lion,

and then to a serpent, then to a leopard, then to a great boar,

and he turned into fluid water, to a tree with towering branches,

but we held stiffly onto him with enduring spirit.

In addition to Homer’s two great poems, much of our knowledge of Greek myth comes from a book called Metamorphoses, written by the Roman poet Ovid in the first decade of the first century A.D. As the title suggests, this book contains dozens of tales of transformation. Sticking with the letter A:

The hunter Actaeon is punished for seeing the chaste huntress-goddess Artemis (the Roman Diana) bathing by being transformed into a stag and devoured by his own hounds.

Aesecus, prince of Troy, jumps into the sea in despair at the death of his beloved nymph Hesperia and is transformed by the sympathetic sea titanness Tethys into a diver bird.

Arachne challenges Athena (Minerva) to a weaving competition and loses to the goddess, who turns her into the first spider.

Metamorphoses’ profound cultural influence extends to the present day, more than 2,000 years after Ovid’s death. The scientific name for spiders (arachnids) and related words such as arachnophobia refer to Arachne’s unfortunate fate. Every time we call someone a narcissist we reference the Greek myth of Narcissus, a handsome young man who spent so long gazing at his own reflection in the water that he transformed into a narcissus flower.

Another Roman book called Metamorphoses (by Apuleius and also known as The Golden Ass) includes the first extant version of Cupid and Psyche, an oft-old story you may know from its many representations in painting or from C.S. Lewis’ retelling in his novel Till We Have Faces. In ancient Greek, psyche meant both ‘butterfly’ and ‘soul;’ Greek has kept the latter meaning and loaned it to languages across the world in the form of words like psychology and psychic.8

Psyche herself is often depicted with butterfly wings in later artworks. “Greek vase paintings sometimes show a butterfly leaving the mouth of a dying person,” Michael Ferber writes in A Dictionary of Literary Symbols. “The idea is that the soul undergoes a metamorphosis at death, leaving behind its earthbound larval state to take wing in a glorious form.” The butterfly’s transformation became a natural symbol for Christian resurrection, as in Dante’s Purgatorio and the poetry of Wordsworth, and also appears in Chinese and Japanese mythologies.

This talk of souls and death may seem like an irrelevant tangent, but the Pokémon anime itself has a kind of insect metamorphosis-as-resurrection, in its way. In the fourth episode, “Challenge of the Samurai,” Ash’s Metapod hurls itself – despite its visible lack of any limbs or other methods of propulsion – in the way of a Beedrill diving down to attack its trainer. The Beedrill breaks its stinger on Metapod, which falls, cracked open, to the ground. Ash picks up the seemingly lifeless creature in his arms, where it bursts into magical light and emerges from its old shell.

To sum up, Pokémon evolution “must never be underestimated” and is crucial to its mythopoesis. Viridian Forest’s insects, which introduce evolution in the games, anime and manga, reflect the series’ earliest inspirations, connect Pokémon to real-world metamorphoses, and inhabit their world’s version of the mythic deepwood.

I would be remiss if I failed to mention Butterfree’s most memorable appearance in Pokémon media, the 21st anime episode “Bye Bye Butterfree.” As the title suggests, it ends with Ash’s tearful farewell to the Butterfree he had raised from its Caterpie childhood; now an adult, it leaves him to join its mate on Pokemon’s equivalent of a truly magical real-life event, the butterfly migration. Ash flash backs to their times together and tears flow from the eyes of young children across the world.

This episode, like Ash’s struggle to tame Charizard, could have begun as a dramatization of something that happens in the Game Boy games. The player who captures a Caterpie in Viridian Forest will likely evolve it into a Butterfree by the time they navigate through the caves of Mt. Moon, where its Psychic-type attack Confusion will prove useful against wild Pokémon and rival trainers. By the time of the player’s second or third gym battle, however, Butterfree will have likely lost its place on the player’s team to new captures with more potential, such as Abra, Bellsprout or Diglett.9 At this point, the player’s choice is between releasing their Butterfree into the wild or keeping it in storage for the rest of the game.

A long-standing internet rumor holds that the original Japanese episode has Ash learning that his Butterfree will die after mating, a detail censored in the English-language dub that makes Ash’s farewell that much more poignant. While this is apparently false (despite resonances with older butterfly folklore, as mentioned above), Ash does react to the loss of Butterfree the way a child would react to the death of a beloved family pet. And like a pet dog or cat, which lives its life much faster than a human being, Ash’s experience of capturing, raising and eventually losing his second Pokémon teaches him a lesson about loss, about transience.

While “Bye Bye Butterfree” is a clear example of the Pokémon anime formula (Ash and friends arrive at a new location, thwart Team Rocket’s attempts at capturing local Pokemon and then depart for further adventures), it uses this formula in support of one of the series’ rare moments of personal growth for its protagonist.

In other words, just as Ash’s taming of Charizard is also a taming of internal monsters, “Bye Bye Butterfree” is an episode of metamorphosis, but for the hero, not his Pokémon.

In a 1999 interview he insisted that he never made these insects fight.

Larimer, Tim and Takashi Yokota. "The Ultimate Game Freak." TIME, Nov. 22 1999. In Pokemon

“Places to catch insects are rare because of urbanization. Kids play inside their homes now, and a lot had forgotten about catching insects. So had I. When I was making games, something clicked and I decided to make a game with that concept.” Tajiri in the aforementioned TIME interview.

Japanese role-playing game.

Non-player character.

Foster, Michael Dylan. The Book of Yokai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore. University of California Press, 2015.

Foster, Michael Dylan. Pandemonium and Parade: Japanese Monsters and the Culture of Yokai. University of California Press, 2009.

While not technically a psychic type, Butterfree does learn the psychic-type attack Confusion upon evolution — a distant, unintentional echo of butterfly as psyche?

21 episodes into the show, Ash’s Butterfree has lost a similar numbers game to newcomers Bulbasaur, Charmander and Squirtle, who each offers more offense.

Man, I love how you have drawn out the elevated within Pokémon. I made an ill-fated attempt at this, but I am thrilled at your success. Well done, I really appreciated this piece.

Nice post! It’s great that you went into Satoshi Tajiri’s love of bugs and how that inspired him to create Pokémon. You wonder if this kind of inspiration from going out playing and exploring is still present in young kids out there