#035: Clefairy

Fairy Tales

Robin: How now, spirit? Wither wander you?

Fairy: Over hill, over dale

Through brush, through briar,

Over park, over pale,

Through flood, through fire;

I do wander everywhere,

Swifter than the moon’s sphere.

And I serve the Fairy Queen,

To dew her orbs upon the green.

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, II.1.1-9.

Like chess, an originally Indian game that passed through and was shaped by Persian, Arabic, Spanish, French, English, American and Russian hands, Clefairy and Clefable are multicultural hybrids combining influences from multiple times and places.

Too many influences, indeed, for a single post. This post will cover the base form Clefairy1 and follow the obvious linguistic thread back to the world of fairy folklore. The sequel, covering the evolved form Clefable, will focus on connections to China’s mythical moon rabbit and to outer space more generally. I will leave a discussion of these creatures’ tranquilizing, soporific song for a future post on their apparent relatives Jigglypuff and Wigglytuff.

The best place to begin is with Clefairy itself and its place in the Pokémon world.

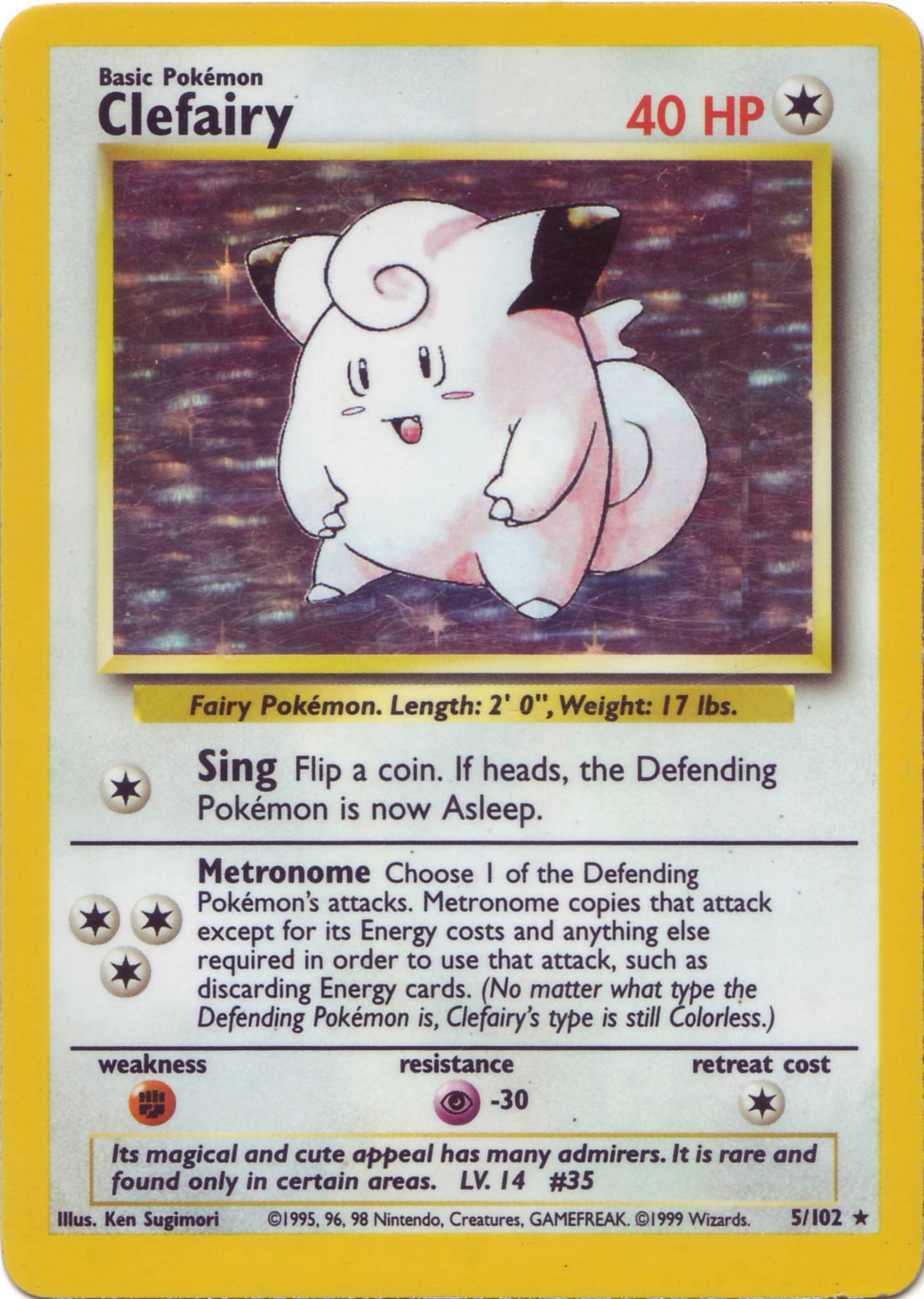

As seen above, the Base Set Clefairy card has both a holographic background and a star rarity symbol, unique attributes for a nonthreatening, unevolved Pokémon.2 The Pokémon Trading Card Game usually reserves these signifiers for two specific categories of Pokémon: powerful, third-stage monsters like Charizard and Venusaur or a handful of designated Legendary Pokémon such as Mew, Mewtwo and the three legendary birds. Placing the cute little Clefairy in this company speaks to its special status among Pokémon.

In a world inhabited by fire-breathing reptiles, ghosts, sea monsters, living piles of sludge and other strange creatures, Clefairy and Clefable are considered particularly special, particularly elusive, particularly legendary.

Pokémon Red and Blue Pokédex entry on Clefairy: “Its magical and cute appeal has many admirers. It is rare and found only in certain areas.”

Red and Blue Pokédex entry on Clefable: “A timid fairy Pokémon that is rarely seen. It will run and hide the moment it senses people.”

Yellow Pokédex on Clefairy: “Adored for their cute looks and playfulness. They are thought to be rare, as they do not appear often.”

Yellow Pokédex on Clefable: “They appear to be very protective of their own world. It is a kind of fairy, rarely seen by people.”

Anime Pokédex: “Clefairy. This impish Pokémon is friendly and peaceful. It is believed to live inside Mt. Moon, although very few have ever been seen by humans.”

Anime Pokédex: “Clefable, an advanced form of Clefairy. These unique creatures are among the rarest Pokémon in the world.”

Professor Oak, The Electric Tale of Pikachu manga: “No one has ever witnessed a Clefairy evolution.”3

As in the TCG, rarity is the key theme here. In The Electric Tale of Pikachu, Ash cannot resist the temptation of a store window advertising “SECRET POKEMON MAP SOLD HERE!” and trades one of his Pokémon for said map, which will allegedly lead him to a Clefairy colony. (He eventually gets there, but only after a long journey during which the map proves to be less than helpful.)

Clefairy’s habitat also sets it apart from other Pokémon. In general, Pokédex entries describe the Pokémon in question as living in a type of environment, in a generic biome like forests, grasslands, caves or oceans. Throughout Pokémon multimedia, however, Clefairy and Clefable are invariably linked to one specific place: to Mt. Moon, the Pokémon world’s equivalent of Japan’s Mount Akagi.

The Pokémon anime’s sixth episode, “Clefairy and the Moonstone,” begins with the narrator informing the viewer that “Many strange and astonishing tales have been told about this mysterious place, and the group's about to discover that all of them are true!”

So, at the outset we have three attributes that set Clefairy and Clefable apart from other Pokémon: they are elusive, seldom seen that rarely interact with human beings; they are associated with a specific location; and that location is the site of myths and legends. Clefairy – Pippi in the original Japanese, Mélofée in French – inherited all of these characteristics from the fairies and, ultimately, from their ancestors, the nymphs.

Who’s Who in Classical Mythology defines nymphs as “female spirits of divine or semi-divine origin — often daughters of Zeus — whom the Greeks believed to reside in particular natural phenomena.”4 Authors Michael Grant and John Hazel list multiple categories of nymphs, including the dryads and hamadryads of groves and forests, the naiads of springs and streams and the nereids and oceanids of the seas.

Like Japan’s yokai, nymphs likely originated as local nature goddesses – as pre-classical Greece’s equivalent of kami – that lived on in mythology after their cults were supplanted by those of the 12 Olympian gods and goddesses. While nymphs are always female,5 they have clear male counterparts in the minor male gods of the winds and rivers that were similarly subordinated to Zeus, Poseidon, Hades and other gods worshipped throughout the ancient Greek-speaking world.

As a result of this process, the classical mythology familiar to has the 12 Olympians as embodiments of the cosmic, universal forces – sky, sea, sun, moon, plant growth, death, wisdom – and the nymphs and minor gods restricted to the local level. The god of a specific river, the dryad of a specific grove or even of a specific tree.

“They resemble the fairies of later folklore,” Grant and Hazel write, “and, like them, could be cruel as well as kind.” And not a power to be taken lightly. In one myth, the Thessalian king Erysichthon cuts down a sacred tree and is cursed with insatiable hunger; he dies in the process of devouring his own body.

Another more familiar illustration of the nymphs’ power comes via possibly the most famous individual nymph in Greek mythology: the nereid Thetis, who married the human king Peleus and made her son Achilles all but invincible by taking him to the underworld and dipping his infant body in the river Styx. Achilles, the greatest Greek hero of the Trojan War, is a half-nymph.

The dragon has retained some of its historic awe; the fairy has not.

The word itself, C.S. Lewis writes in The Discarded Image, is now “tarnished by pantomime and bad children’s books with worse illustrations.”6 Fairies’ close relatives – the other little people of the British Isles – have hardly fared better. Gnomes are kitschy lawn ornaments; elves sit on the shelf or accompany Santa at the local mall; leprechauns sell sugary cereal or play the monster in schlocky horror movies; kobolds are entry-level World of Warcraft enemies with meme-worthy bad grammar. With a few exceptions, such as Morgan le Fay, Maleficent or Tolkien’s elves,7 fairies and their relatives have childish, garish associations.

Attempting to understand what fairies meant in the premodern world involves dropping some of this baggage: seeing them not as cute and doll-like but as nature spirits, as what nymphs evolved into in a Christianized Europe.

The entry on fairies in A Dictionary of English Folklore begins by emphasizing the word’s loose definition:

A range of non-human yet material beings with magical powers. These could be visible or invisible at will, and could change shape; some lived underground, others in woods, or in water; some flew.8

Fairies and fairy-adjacent creatures ranged from Scotland’s brownies, said to infiltrate farmhouses and perform domestic chores, to the shapeshifting Irish púca and the knockers said to knock on the walls of Welsh and Cornish mines. Elves, Borges writes in The Book of Imaginary Beings, were imagined as “tiny and sinister” creatures that “take pleasure in minor acts of devilry.”

A few aspects of fairy folklore have survived to the present day.

As silly as it might be, the idea of the tooth fairy reflects one aspect of more authentic fairy folklore: fairies as unseen beings who can easily infiltrate human spaces. (Premodern and early modern fairies, as we’ll soon see, had a much more sinister interest in young children.)

We call the visible fruiting bodies of underground fungi fairy rings because premodern people imagined them to be the magical traces of circular fairy dances.

Contemporary Irish people still refer to their country’s ancient hillforts and passage tombs as fairy forts for the same reason we refer to the cyclopean masonry of bronze age Greece: because premodern people imagined that mythical creatures built these incredible structures. (Unlike most ruins throughout the world, Irish fairy forts have been mostly undisturbed throughout the centuries thanks to superstitions about curses and passageways to the underworld.)

Dictionary of English Folklore author-editors Simpson and Roud mention a Cornish origin story for the creatures: “angels who refused to side with either God or Lucifer when the latter rebelled, and so, being ‘too good for hell and too bad for heaven,’ were thrown down to earth and lived where they happened to fall.” Lewis identifies three other folkloric origins in The Discarded Image: fairies as ghosts, fairies as another intelligent race distinct from humans or angels; and fairies as demons, which was the opinion of England’s James I, who moonlighted as a demonologist. (Neither ghosts, nor fairies, nor demons appear in medieval bestiaries; they were considered a different kind of being than the beasts and birds.)

The idea of a fairy as a kind of demon – miles away from our Disney images of Tinker Bell and fairy godmothers – speaks to the fear it once inspired. In the British Isles, people came up with a series of euphemisms to avoid speaking their name: the little people, the good folk, the fair family, the little fair men.

Like their ancestors, the nymphs, the fairies embodied the fickleness of nature, which could be catastrophic. Mythical creatures are a mirror for human hopes and fears; fairies seem to have embodied one of the greatest fears of a world with high child mortality.

The word changeling, Samuel Johnson writes in his own famous dictionary, “arises from an odd superstitious opinion, that the fairies steal away children, and put others that are ugly and stupid in their places.”9 Johnson, writing in cosmopolitan mid-18th century London, dismisses the fear of child abduction by fairies as “an odd superstitious opinion;” this fear was very real for his ancestors and even for his contemporaries across the Irish Sea.

“Mothers and babies were thought to be especially liable to be abducted by the fairies,” E. Estyn Evans writes in Irish Folk Ways.

protective charms were hidden in a baby’s dress or placed in the cradle… The old custom of dressing boys in girls’ clothes, in long frocks, until they were ten or eleven years of age has been explained as a means of deceiving the fairies, who were always on the lookout for healthy young boys whom they could replace by feeble ‘changelings.’10

Shakespeare’s fairy queen Titania takes possession of “a lovely boy, stol’n from an Indian king/ She never had so sweet a changeling.” William Butler Yeats, whose interest in the occult extended to an actual belief in fairies, takes up this theme in his poem “The Stolen Child:”

Come away, O human child!

To the waters and the wild

With a faery, hand in hand,

For the world's more full of weeping than you can understand.11

At around the same time his eventual patron James I classified fairies as demons in his demonology, William Shakespeare had Mercutio deliver a soliloquy about the fairy Queen Mab riding a chariot made out of a hazelnut, with wheels made of spider’s legs and a gnat as a driver.

“The diminutive being, elf or fairy, is (I guess) in England largely a sophisticated product of literary fancy,” J.R.R. Tolkien writes in On Fairy-Stories. “I suspect,” he continues

that this flower-and-butterfly minuteness was also a product of ‘rationalization,’ which transformed the glamour of Elfland into mere finesse, and invisibility into a fragility that could hide in a cowslip or shrink behind a blade of grass.12

In an age of exploration, colonization, globalization, mythmakers were simply running out of territory, out of semi-legendary distant lands to house mythical creatures. So, in the case of fairies, they shrunk them down to a size small enough to be hidden in the local forest.

Tolkien’s fellow Inkling C.S. Lewis argues that fairies’ fear-inspiring, demonic qualities contributed to a more metaphorical cutting down to size. As a parallel, consider how devils have become comedic figures despite (or, more probably because) their status as symbols of ultimate evil: the flatulent buffoons of medieval mystery plays; the Halloween costume of horns, pitchfork and red tights; the shoulder devil advising cartoon characters to be naughty; the dark comedy of Lewis’ own Wormwood and his dear uncle Screwtape.

In the same way, the ghostly, demonic, child-abducting fairies became supporting characters in Shakespearean comedy.

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the ur-text for the modern fairy, the fairy king Oberon distinguishes himself and his subjects from “damned spirits.” After Shakespeare, the deluge of child-friendly fairies: the fairy godmother in Charles Perreault’s Cendrillon (1697), the definitive Cinderella story; The Blue Fairy in Carlo Collodi’s The Adventures of Pinocchio (serialized 1881-1882); Andrew Lang’s rainbow-colored Fairy Books for children (1889-1913); Tinker Bell in J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan (1904); Kipling’s Puck of Pook’s Hill (1906) and its sequel Rewards and Fairies (1910); Walt Disney’s animated takes on most of these stories.13

And, at the end of this story, we have Clefairy, a fairy even rounder, cuter, cuddlier and more infantile than Disney fairies.

Besides the name itself, does Clefairy reflect anything authentic, anything essential about the folkloric fairy? Or does it represent a final devolution away from mythic roots and into pure commercial kitsch?

The answer to both questions has to be yes, to some extent. Clefairy is kitsch, part of a colossal, colossally successful global media empire. Pink, soft, round, big-eyed: tailor-made for translation into a plush doll. So doll-like, in fact, that it’s already a doll in the Pokémon world; the “magical and cute appeal” mentioned in the Pokédex has apparently made the Clefairy doll that world’s equivalent of our teddy bear.

But, just as the teddy bear reflects the bear’s special, totemic status in the (earth) human imagination, the Clefairy doll reflects a Pokémon with a special place in its world.

In The Electric Tale of Pikachu, Ash’s map eventually leads him to a small, hidden community of Clefairy on a remote mountain. Alongside Professor Oak and Oak’s aide Bill, Ash becomes one of the first three humans to witness the Clefairy’s coming-of-age ritual: Clefairy old and brave enough to venture away from home are ceremonially presented with the Moon Stones that evolve them into Clefable.

The animated version of Ash makes a similar discovery in the anime’s sixth episode; both Ashes ultimately decide not to pursue their original goal of capturing a Clefairy, presumably because they recognize the creatures’ intelligence and communal bonds. Both media, then, present a community of intelligent, diminutive creatures living in their own hidden communities, little worlds out in nature exist in parallel with the human world and rarely come into contact with it. In other words, something very reminiscent of fairies in the pre- and early modern European imagination.

In that anime episode, Ash and his companions watch Clefairy dancing around the monolithic Moon Stone, under the light of a full moon. Kawaii and kiddie as this scene might be, it does present an archetypal fairy image: oneiric, Shakespearean, the magical moonlit dance that leaves behind a ring of mushrooms in the morning.

Returning to the original games, Clefairy’s signature attack represents one last trace of fairies and of their ancestors, the nymphs. Both creatures embody the fickleness of nature, the seemingly random way it gives and takes a way, offering a good harvest one year and a famine the next, or decades of stability punctuated by a plague or natural disaster. Thus nymphs and fairies, intelligent and amoral, at turns helpful and harmful, acting according to their own unknown motivations.

Clefairy and Clefable’s signature move is Metronome, an attack with the effect of another, randomly selected attack. The player might get a one-hit KO attack that immediately wins them the battle, Magikarp’s completely ineffectual attack Splash, or anything in between. Metronome, in its small, gamified way, speaks to one core aspect of what fairies once meant.

Stars signify the rarest Pokémon cards, with circles for the most common cards and diamonds for intermediate cards.

Ono, Toshihiro. Pokémon Graphic Novel, Volume 1: The Electric Tale Of Pikachu!. VIZ Media, 1999.

Grant, Michael and John Hazel. Who’s Who in Classical Mythology. 1973. Oxford University Press, 1993.

The word itself also means “young bride” in Greek.

Lewis, Clive Staples. The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature. 1964. Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Tom Bombadil and his wife Goldberry also have clear parallels with folkloric fairies.

Simpson, Jacqueline, and Steve Roud. A Dictionary of English Folklore. Oxford University Press, 2000.

A few weeks ago, another Substacker asked me to a share a post that represents me on the page. I think it has to be quoting Samuel Johnson in a post about Pokémon.

Evans, Emyr Estyn. Irish Folk Ways. Routledge & Paul, 1957.

You might remember this poem from the Steven Spielberg/Stanley Kubrick film A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), a film with fairy motifs both obvious (Pinocchio’s Blue Fairy) and subtle (David, the robotic substitute for a real boy, as a futuristic changeling).

Tolkien, J.R.R. "On Fairy-Stories." Poems and Stories. Houghton Mifflin, 1994.

Fairies did have a brief second life as actual mythical creatures/cryptids during the late 19th and early 20th century fascination with occult. As previous mentioned, W.B. Yeats apparently believed in their existence. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was taken in by the Cottingley Fairies, an obvious hoax that his most famous creation Sherlock Holmes would have seen through.

If I recall correctly, aren't there legends within the Pokemon universe that Clefairy/Clefable originated from outer space?

If so, it makes me think of theories by some UFOlogists that fairy myths represent pre-modern interpretations of extra-terrestrial encounters, i.e. magic being advanced technology, the abduction narrative.

Probably not intentional on the creators' part, but an interesting parallel to consider.

I’m continually impressed by the depths of scholarship and thought behind your Pokemon essays!

I was too old for the original Pokemon craze and have let them stay off my radar since then, so every time I read another installment of Necessary Monsters, i something new (and yet oddly familiar) is added to my life.

It’s particularly interesting to learn how the writers of Pokemon media mine both the Japanese and Western mythic menagerie— and to discover the ways they complement one another.