#025: Pikachu part 2

Wee, sleekit, cowrin, tim'rous beastie

There is a limit to the number of tough-looking Pokémon one can make, so we made weird Pokémon, huge Pokémon, mechanical Pokémon...and after considering all these variations, I thought, ‘We need more cute ones.’

Ken Sugimori, Pokémon co-creator, illustrator and creature designer

Mickey Mouse. Jerry Mouse. Mighty Mouse. Stuart Little. Speedy Gonzalez. Reepicheep. The Rescuers, The Great Mouse Detective, An American Tail, Pinky and the Brain, “Three Blind Mice,” “Hickory Dickory Dock.” How and why have mice so infested English-language children’s media?

Real-life mice, except in the niche eyes of a few pet owners, are not cute or cuddly. We see them as pests, invading our homes and other human spaces, or as vectors of disease. We buy mousetraps or hire exterminators to get rid of them; we buy a variety of products from ultrasonic frequency generators to powdered fox urine to stop them from coming back.

Nonetheless, we also make them protagonists of children’s stories and corporate and cultural mascots – and not just in the western world. In China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Japan, Vietnam, various diasporas and other communities that use the Chinese Zodiac, the ill-fated year of 20201 was the most recent Year of the Rat/Year of the Mouse, an occasion celebrated with a plethora of cute mice mascots on red envelopes, t-shirts and other products. People born in the year of the rat – which may include you if you were born in 2008, 1996, 1984, 1972 or 1960 – are, in the words of chinesenewyear.net, “clever, quick thinkers” who are “intuitive, versatile, and quick-witted” and “always on the lookout for any opportunities that may not be readily visible to others.”

This characterization – you can find something similar in any horoscope you choose to read – reflects the mouse or rat’s role as a trickster2 in Chinese folklore. In the origin myth of the zodiac itself, the Jade Emperor3 challenges the animals to a race which will determine who will be included in the zodiac. After tricking the kind but dimwitted ox to carry him across a river, the rat/mouse wins the race; to commemorate this victory, the 12-year zodiac cycle begins with the Year of the Rat/Mouse.4

This infestation is also very old, as you’ve probably ascertained from this Chinese zodiac story. “The Country Mouse and the City Mouse” originates with the ancient Greek storyteller Aesop, who wrote several other fables about mice and died more than 2,500 years ago. Centuries before Aesop, Middle Kingdom Egyptians told a fable about a clever, mischievous mouse who becomes vizier.5 An unjust ruler, the mouse is not only dismissed from office by the pharaoh but banished from the earth’s surface, which provides a mythic explanation of why mice live in underground burrows.

So, why have stories about mice become such an important part of folklore and, more recently, of children’s fiction?

I can think of two overlapping answers.

First, the common house mouse (Mus musculus) is, like Homo sapiens, one of the few species found on every continent. Thriving in close proximity to humans, the mouse has spread to almost every country on the planet, putting it into contact with many different cultures in many different times and places.6 It is, in other words, a globally local animal with mythical or folkloric resonances in most cultures: a strong foundation for a global cultural icon.

Second, the choice of a mouse as a protagonist transforms the otherwise normal, even banal setting of a human home into a landscape full of discovery and danger. Think of, for instance, how ordinary suburban living rooms, kitchens and backyards serve as the weapon-rich terrain for epic slapstick battles in the Tom & Jerry cartoons.

This mouse’s eye view of the world has obvious similarities to that of young children, who also perceive the spaces around them as places to explore, as any parent reading this can attest to. For them, as for the anthropomorphic mice of fiction, little adventures await in place that have become disenchanted, for the most part, for us adults. This congruity offers another major reason for the mouse’s appeal to children, one enhanced by a common trope in mouse folklore and fiction.

If I asked you to name a piece of western mouse folklore, you’d probably respond to elephants’ supposed fear of mice, an enduring myth – in both that word’s true sense and modern, degraded sense of “widely believed falsehood” – that modern experts still feel the need to debunk. Like a few myths featured on Necessary Monsters, this fear seems to have originated with the Roman polymath and volcanic eruption victim Pliny the Elder, who recorded it in his Naturalis Historia (77-79 CE.), and then to have been codified in the medieval bestiaries.78

We remember elephants’ alleged fear of mice, I think, because it provides the most dramatic illustration of the archetypal mouse as David overcoming Goliaths: the Chinese zodiac mouse, as we’ve seen; Mickey Mouse triumphing over Pete; Jerry and Speedy Gonzalez outsmarting their feline nemeses. To mix animal imagery, the mouse is the perfect underdog, plucky and resourceful.

As with mouse tales’ transformation of ordinary spaces into sites of adventure, this mouse-underdog has obvious imaginative appeal to children: the smaller, smarter creature triumphing over its larger, stronger adversaries.

Pikachu has clearly inherited much of its DNA from this mouse archetype. Like cartoon mice outsmarting cats or bestiary mice scaring off elephants, Pikachu often triumphs over much larger and more intimidating adversaries in the anime and manga. For instance, Ash and Pikachu lose their first match against Pewter City gym leader Brock in the anime’s fifth episode, “Showdown in Pewter City;” Pikachu is overpowered by Brock’s Onix, a giant rock snake that constricts its opponents like an anaconda. They win their rematch through strategy, by unleashing a thunderstorm that sets off the gym’s fire sprinklers. As a half-rock, half-ground hybrid, Brock’s Onix is doubly weakened by this exposure to water, enough to become vulnerable to Pikachu’s attacks.

Ash and Pikachu win their third gym badge in a similar way. After first losing to Lieutenant Surge’s Raichu, which overpowers Pikachu, Ash considers using a thunderstone to evolve Pikachu into his own Raichu. Deciding to keep Pikachu as it is, Ash uses its superior agility to outrun the bulkier Raichu, tiring it out and eventually winning the battle.

Similar narratives play out in Toshihiro Ono’s Electric Tale of Pikachu manga, such as Pikachu defeating an attacking Fearow in the first chapter and Team Rocket’s Arbok and Weezing in the eighth. Ono’s manga culminates in a battle between Ash and the much more experienced Drake for the Orange Islands championship. The final chapter sees both trainers down to their last Pokémon: Pikachu for Ash and the much, much larger Dragonite, hitherto undefeated, for Drake. At first, it looks like Dragonite’s winning streak will continue. As the announcer puts it, “Pikachu is giving its all, but to no avail! It’s a total mismatch! It’s almost like a child vs. an adult!”9 But Ash and Pikachu win, through cunning, over one last Goliath.

In his own words, Pokémon illustrator and lead creature designer Ken Sugimori “designed with a boy’s heart,” creating monstrous Pokémon inspired by kaiju such as Godzilla and his various friends and enemies. To compliment Sugimori’s approach, the fledgling (and all-male) Game Freak team hired character designer Atsuko Nishida to join their four-person design team in the hopes that she could create cuter characters appealing to female gamers.

This hire turned out to be one of the most successful moves in Pokémon history; Nishida’s decades of work at Game Freak includes dozens of Pokémon designs, including the first-generation starters Bulbasaur, Charmander and Squirtle, as well as more than 400 Pokémon card illustrations and designs for human anime characters.10 “With the straight-on cute Pokémon,” Sugimori once told an interviewer, “you can leave those to Nishida and you’ll never go wrong that way.”

After joining Game Freak, Nishida received the assignment of designing an electric Pokémon with two evolutions. Initially inspired by Japanese mochi cakes called daifuku, she imagined, in her words, “a creature in the shape of a long daifuku with ears sticking out.” Since it would be an electric Pokémon, she started playing around with pika-pika, the Japanese onomatopoeia for glittering or sparkling, and came up with the name Pikachu.

“I didn’t draw an illustration on paper,” she would later recall,

but went straight to the computer screen and punched in the dots. Using dots to create the face of this dumpling-shaped creature with no definition between its head and body! At the time, I was obsessed with squirrels. I didn’t own a squirrel, but I wanted to because I thought its movement was comical. It was here that I was inspired to make Pikachu store electricity in its cheek pouches. When hamsters store food, their entire body puffs up, but with squirrels, it’s just their cheeks.

Game Freak director Satoshi Tajiri, observing that chu can mean ‘squeak’ in Japanese, suggested that Nishida make Pikachu into an ‘electric mouse,’ while fellow designer and self-appointed ‘cuteness supervisor’ Koji Nishino suggested that she make it even cuter. Nishida gave the creature its lightning bolt-shaped tail to make its back sprite11 more interesting and to visually communicate its Electric elemental status. Nishida also designed two evolved forms for Pikachu: Raichu, which made the final game, and Gorochu, a fanged, vampire-inspired creature that was eventually cut.

Pikachu’s design was well-received by Nishida’s colleagues, especially Nishino, who felt so possessive of it that he decided to make it rare and hard to capture in the game. This strategy backfired as Pikachu’s rarity piqued the interest of players and spawned the publication of unofficial guides to capturing it.

The writers and producers of the Pokémon animated series found themselves in a quandary during pre-production. Which Pokémon should the protagonist choose as his starter? The Game Boy players could choose between Bulbasaur, Charmander and Squirtle; if he chose one of these creatures, would the other two-thirds of children feel put out because they’d chosen the “wrong” Pokémon?

The anime protagonist (Satoshi in the original Japanese) would instead oversleep, miss out on receiving one of those three, and have to go with a fourth option. Several small, cute, yet potentially powerful creatures emerged as possibilities, with the final choice being between Pikachu and Clefairy. Pikachu was chosen for two reasons. First, the pink, kawaii Clefairy was thought to appeal primarily to girls, whereas Pikachu was seen as appealing equally to boys and girls. Second, Pikachu already had grassroots popularity due to its rarity, as previously mentioned. The anime producers “wanted to feature Pikachu,” according to Game Freak developer and composer Junichi Masuda, “because Pikachu at the time was really popular amongst kids in school. It is a hard-to-find Pokémon, so kids knew about it.”

By the time Pokémon came to America in 1998, Pikachu was the focus of branding and marketing efforts: the Tamagotchi competitor called the Pokémon Pikachu; the Nintendo 64 game Hey You, Pikachu! (1998 in Japan, 2000 in North America), which let players talk to Pikachu with a special microphone peripheral; a new, Pikachu-focused version of the Game Boy games known as Pokémon Yellow Version (1998 in Japan, 1999 in North America).

Interaction with Pikachu was the selling point of Yellow, which sold more than 14 million copies worldwide; to quote the blurb on the back of the box, “the shockingly cute Pikachu tags behind you as you search the enormous world for monsters to train and evolve.” While the gameplay itself was almost identical to that of Red and Blue, save for a few changes and additions to align its world with that of the anime, the increased presence of Pikachu was enough to make it an international bestseller.

You can, of course, say the same about a plethora of Pikachu merchandise, from stuffed animals to t-shirts to backpacks to hundreds of trading cards, including some of the rarest and most expensive.

As a cultural icon, there is only one other mouse in Pikachu’s league, and I will end this post with that comparison – and with what it says about Pikachu.

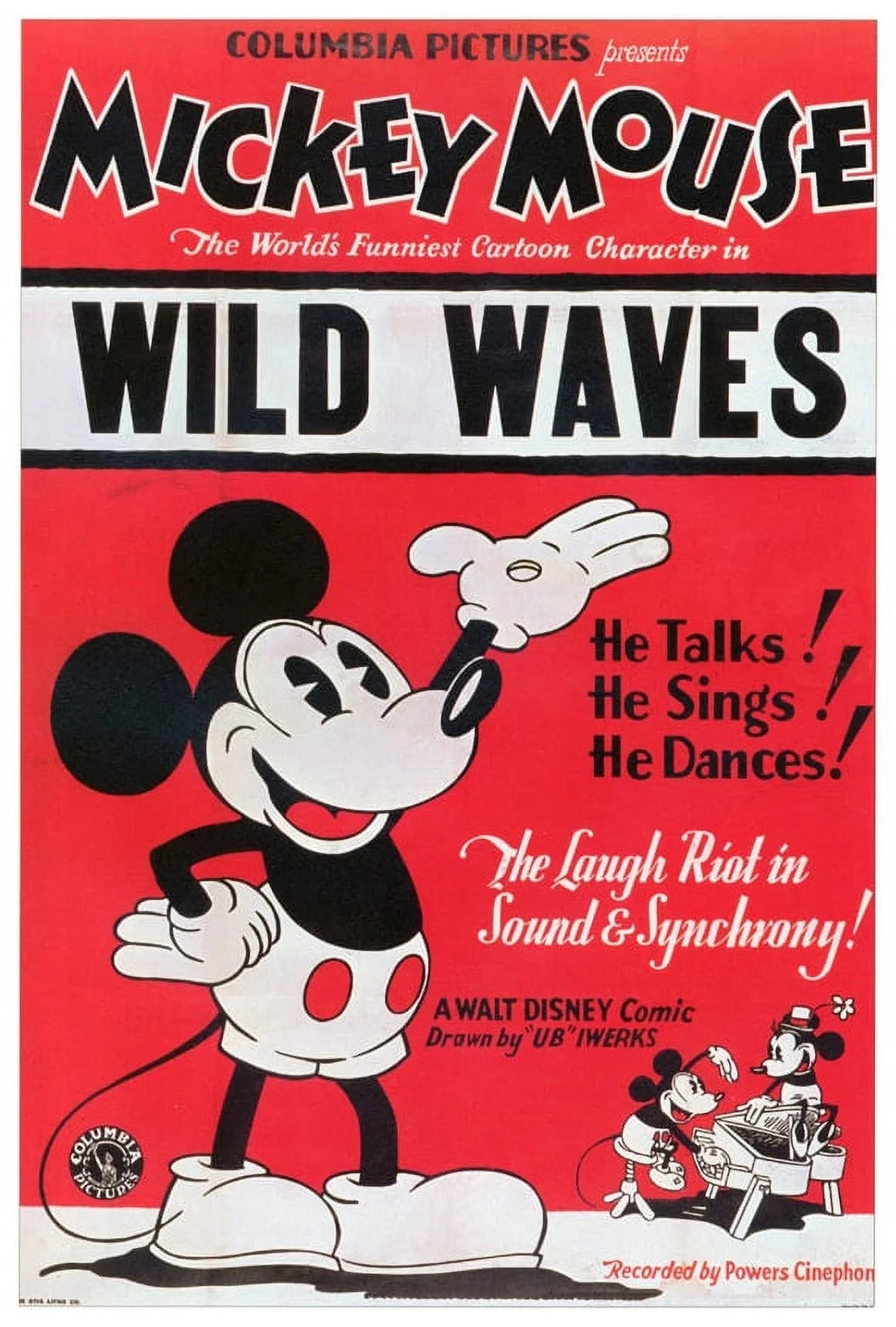

“I only hope that we never lose sight of one thing — that it all started with a mouse,” said Walt Disney in an oft-quoted, self-mythologizing statement. While not, strictly speaking, true, as Disney began making cartoons eight years before Mickey Mouse’s debut, it does reflect Mickey’s central role in Disney’s cultural and economic ascent in the 1930s.

Despite his name, however, Mickey Mouse almost never behaves like a mouse. In one early cartoon, When the Cat's Away (1929), Mickey and Minnie — both actually mice-sized — lead a group of similar-looking mice into a house, where they engage in various musical antics. This cartoon is an anomaly and even somewhat uncanny because Mickey has basically behaved like a human being from Steamboat Willie (1928) to the present. In the words of Walt Disney himself, “when people laugh at Mickey Mouse, it’s because he’s so human, and that is the secret of his popularity.” Mickey talks, lives in a house, drives a car, has a pet dog, goes out with his girlfriend and pursues a variety of career opportunities, from taxi driver to bandleader to apprentice sorcerer.12

As a child, I didn’t see any incongruity in visiting Disneyland and meeting adult human-sized Mickey and Minnie. They were anthropomorphic enough to make sense in a real-life setting, and at that size. On the other hand, I think I would have reacted very differently to a Pikachu mascot played by an adult human in a costume; it would have seemed grotesque, misshapen, wrong, especially if it signed an autograph for me.

The difference is that Mickey Mouse lives in a house and owns a pet, whereas Pikachu lives in the woods and is a potential pet. None of Pikachu’s Pokédex entries, for instance, mention anything like a pseudo-human intelligence. Instead, they focus on Pikachu as part of a natural ecosystem. “It lives in forests away from people,” according to the Pokémon Stadium Pokédex. “When several of these Pokémon gather, their electricity could build and cause lightning storms,” in the words of the Red and Blue Pokédex. In the Pokémon Adventures manga, Red’s Pokédex describes Pikachu as “forest dwellers… few in number and exceptionally rare.”13 The Pokédex in Toshihiro Ono’s Electric Tale of Pikachu manga gives this description:

An electric mouse Pokémon.

Habitat: Forests and woodlands

Diet: Mainly fruit

Distinguishing features: Has an electric generator on each cheek.

Beware of electrocution!14

The Electric Tale of Pikachu begins with the title character as a wild animal, an inhabitant of a forest near Pallet Town who gets into Ash’s house and begins gnawing the electrical wires. In Pokémon Adventures, Pikachu is a notorious, feral pest that steals food from the residents of Pewter City; the protagonist Red has capture and tame it. In the anime, Ash receives an unruly, disobedient Pikachu from Professor Oak: a creature who refuses to enter its Pokéball or obey any of its new trainer’s orders. For all three protagonists, then, an early step of the journey is the taming of a wild or semi-wild Pikachu.

This wildness — in contrast to Mickey’s anthropomorphism — speaks to why Pikachu became the most successful and iconic Pokémon.

Consider Pikachu’s black and yellow color scheme. In our world, this color combination often signals a poison or venomous animal: wasps, bumblebees, rattlesnakes, pit vipers, fire salamanders, yellow-banded poison dart frogs, yellow garden spiders. Biologists call this aposematism, the use of signals such as bright, contrasting colors to advertise an animal’s toxicity/unpalatability/other undesirable attribute and thus deter potential predators.

Pikachu’s color scheme seems to serve this same purpose in the Pokémon world. As Ash finds out, repeatedly, Pikachu are quick to Thundershock anyone or anything they perceive as a threat, or as an annoyance. In the words of the Electric Tale of Pikachu Pokédex, “beware of electrocution!” This is a wild animal with a wild animal’s instincts.

J.R.R. Tolkien once described Tom Bombadil, the most enigmatic character in The Lord of the Rings,15 as “the spirit of the (vanishing) Oxford and Berkshire countryside.” Like Tolkien, Satoshi Tajiri created his mythopoeic world as a response to and symbolic preservation of the vanishing countryside of his childhood. If any Pokémon can be described as the spirit of the vanishing Kantō countryside, it would have to be Pikachu, for its paradoxical combination of nature at its smallest and commonest with nature at its most epic, most supernatural. Chu, the squeaking of one of the planet’s most ubiquitous animals, the mouse that invades our homes and reminds us that, despite our efforts, we cannot opt out of the natural world.16 Pika-pika, electrical sparkling, a synecdoche for the thunder and lightning that still retains some of its cosmic, mythical, numinous meaning.

Combined, they create the perfect fantasy pet, plucky and cute, with power to unleash the elemental forces of nature. The uncontrollable made controllable and kawaii; wild nature in small, a child-friendly package; the ideal imaginary companion for an imaginary adventure.

More precisely, the period between January 25th, 2020 and February 11th, 2021.

Peow, See H. "A Comparative Study of Malay and Chinese Trickster Tales: Sang Kancil, the Rabbit and the Rat 1." Kajian Malaysia, vol. 34, no. 2, 2016, pp. 59-73. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/comparative-study-malay-chinese-trickster-tales/docview/2038212093/se-2, doi:https://doi.org/10.21315/km2016.34.2.3.

A supernatural figure still actively worshipped by practitioners of Taoism and Chinese folk religions.

There are many versions of this story. In one, the rat tricks his best friend, the cat, into oversleeping and missing the race: a mythical explanation of both the cat’s absence from the zodiac and the cat-mouse predator-prey relationship, here imagined as generations of mice taking revenge on their ancient friend-turned-enemy. In another variation, both rat and cat ride on the ox’s back across the river until the rat pushes the cat into the water.

Mercatante, Athony S. Who’s Who in Egyptian Mythology. 1978. MetroBooks, 2002.

Shibasaki, Shota, Ryosuke Nakadai, and Yo Nakawake. "Biogeographical Distributions of Trickster Animals." Royal Society Open Science, vol. 11, no. 5, 2024, pp. 1-13. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/biogeographical-distributions-trickster-animals/docview/3066609277/se-2, doi:https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.231577.

White, T.H. The Book of Beasts: Being a Translation from a Latin Bestiary of the 12th Century. 1954. Dover, 2010.

Some medieval mouse folklore has not survived in popular memory. Per White’s translation, “the liver of these creatures gets bigger at the full moon, just as certain seashores rise and fall with the waning moon.”

Ono, Toshihiro. Pokémon Graphic Novel, Volume 4: Surf's Up, Pikachu. VIZ Media, 1999.

Nishida’s other designs include Vulpix and Ninetales, the Oddish-Gloom-Vileplume family, Ponyta and Rapidash, Vaporeon, Espeon, Umbreon, Leafeon, Glaceon, and Sylveon.

The Disney canon includes a number of significantly more mouselike mice – the protagonists of the Silly Symphonies The Flying Mouse and The Country Cousin; Timothy Mouse in Dumbo; Jacques and Gus in Cinderella, the titular protagonists of The Rescuers – that look very different than Mickey and Minnie.

Manga writer Hidenori Kusaka seems to have drawn on the creature’s artificial scarcity in the Game Boy games due to Nishino’s possessiveness.

Ono, Toshihiro. Pokémon Graphic Novel, Volume 1: The Electric Tale Of Pikachu!. VIZ Media, 1999.

And, of course, notably absent from the film adaptations.

As previously mentioned, this is exactly how The Electric Tale of Pikachu begins.

“This mouse’s eye view of the world has obvious similarities to that of young children, who also perceive the spaces around them as places to explore, as any parent reading this can attest to. For them, as for the anthropomorphic mice of fiction, little adventures await in place that have become disenchanted, for the most part, for us adults.”

Too real..

Honestly, I don't think this is something I would have ever thought about. Mice are magical, mystical, and even cute. When I think about it now, mice have been present in my life and mostly framed as innocent. Heck, they're even Michelin Star Chefs. On the flip side of that, rats are monstrous. Now, I wonder about that.