#025: Pikachu part 1

Of Mice and Thunder Gods

Start by picking up a palm-size Nintendo Game Boy, insert the proper cartridge and switch it on. Soon, a creature with a lightning-bolt tail bounces through an animated sequence, pops a cute grin and yelps, ‘Pikachu!’ You have met the most popular of the Pokémon, a creature — part cherub and part thunder god —that is the most famous mouse since Mickey and Mighty.

Beware of the Pokemania,” November 1999 Time cover story by Howard Chua-Eoan and Tim Larimer

It’s 1999. You’re one of many children enthralled with the Pokémon anime and receive a copy of Pokémon Red or Blue, perhaps as a Christmas or birthday present. You of course want to begin your quest to catch ‘em all with the show’s star, Pikachu.

But Pikachu is only a minor presence in the game. Unlike Ash in the anime, the player character cannot choose Pikachu as a starter. No major characters, such as gym leaders or Elite Four members, use Pikachu on their teams; no NPC mentions Pikachu-related lore or legends. It can only be encountered in two of the game’s many locations.1 It is just one of many Pokémon, and a good deal less prominent than some of the other 150.

How did this minor video game character become the most popular Pokémon, the face of the entire series?

Of the 1,025 Pokémon that exist at the time I’m writing this, Pikachu remains by far the most famous. When it came time to celebrate Pokémon’s 10th, 20th and 25th anniversaries, there was only one option for the logos:

Pikachu has appeared on more than 200 Pokémon cards, as a Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade balloon (every year from 2001 to the present), on the cover of Time and The New Yorker and on the island of Niue’s $1 coin. It has appeared in every single Pokémon movie and anime episode. It became the first internationally known Pokémon after a notorious incident involving the hospitalizations of hundreds of children. The retinas you’re currently using to read this post function, in part, due to a photoreceptor protein called Pikachurin, which was discovered by Japanese scientists and named after the Pokémon. Pikachu is inescapable.

I will attempt to explain why in this post and its upcoming sequel; if any individual Pokémon deserves multiple Necessary Monsters posts, it’s this one.

The best place to start might be the name itself, because Pikachu is one of just a handful of Pokémon to keep its original Japanese in every translation. That name comes from two onomatopoeic Japanese words: pika, the sound of electrical sparking, and chuchu, a mouse’s squeak.

These two words provide the structure for my analysis of Pikachu. This post will analyze Pikachu as an electrical elemental, exploring lightning and thunder as motifs in mythology and fiction, while the next post will look at it as a mouse, concluding with a discussion of Pikachu’s design process and a comparison to the most iconic of cartoon mice.

Even in our modern, technologically advanced society, a thunderstorm can still evoke primal, numinous awe. It can be overwhelming enough when observed from a safe, warm home: flashes of light, booming thunder, pouring rain, dogs barking, frightened babies crying. For someone caught out in the storm, it can be truly sublime, in the Romantic sense, awful in that word’s original meaning of full of awe.

When I was an undergrad, my professor of classical art history once told us a story about a sublime experience she had as a student. As an art history student visiting Rome, she of course made a pilgrimage to the Pantheon, the domed temple built during the reign of Hadrian to house statues of all the Olympian gods. On the day she went, a storm broke out over Rome and, as she saw rain pouring through the dome’s oculus and heard the thunder echoing through the temple, she had a profound intuitive sense — connaitre rather than savoir, kennen rather than wissen, conocer rather than saber — of why the Romans crowned Jupiter the thunderer as the king of the gods.

This story resurfaced in my mind when I had a somewhat similar experience in Germany. In the Black Forest I hiked deep into the woods, far from shelter or any artifact of human civilization, when rain started falling, lightning started thrashing, and thunder boomed. As the lightning hit nearby trees and the thunder came closer and closer, my thoughts turned to Zeus, to Jupiter, and, considering my Germanic surroundings, to Thor’s hammer Mjölnir.

These ancient thunder gods continue to influence our lives despite our lack of any actual belief in them. You may, for instance, be reading this on a Thursday: on Thor’s day. The French jeudi and the Spanish jueves both come from the Latin Jovis dies, ‘Jupiter’s day,’ while German speakers call Thursday Donnerstag, literally ‘thunder day.’

Chris Hemsworth’s Thor has of course grossed billions at the global box office, to say nothing of theme park characters and merchandising tie-ins. If you visit Scandinavia, you may meet someone with a name like Thoresson or Thuresson, son of Thor.

And, of course, if you look up at the sky on a clear night you might see the gas giant Jupiter, king of planets. In a wonderful synchronicity of myth and science, the largest storm in the known universe, the Great Red Spot, is on Jupiter. Larger than the earth, this thunderstorm has raged for at least three centuries.

Zeus, Thor and Jupiter are only three faces of a much older, archetypal thunder god whose worship was spread across Europe and Asia by the epic migrations of the ancient Indo-Europeans.2 In ancient India he took the form of the storm god Indra, who, like Zeus and Jupiter, wields the thunderbolt and dethrones his father as king of the gods. (His father, the god of the sky, is called Dyaus or Dyauspitar, names clearly related to Zeus and Jupiter.) Pagan Slavic mythologies had a thunder god called Perun or Perkunas, again with roots in proto-Indo-European myth.

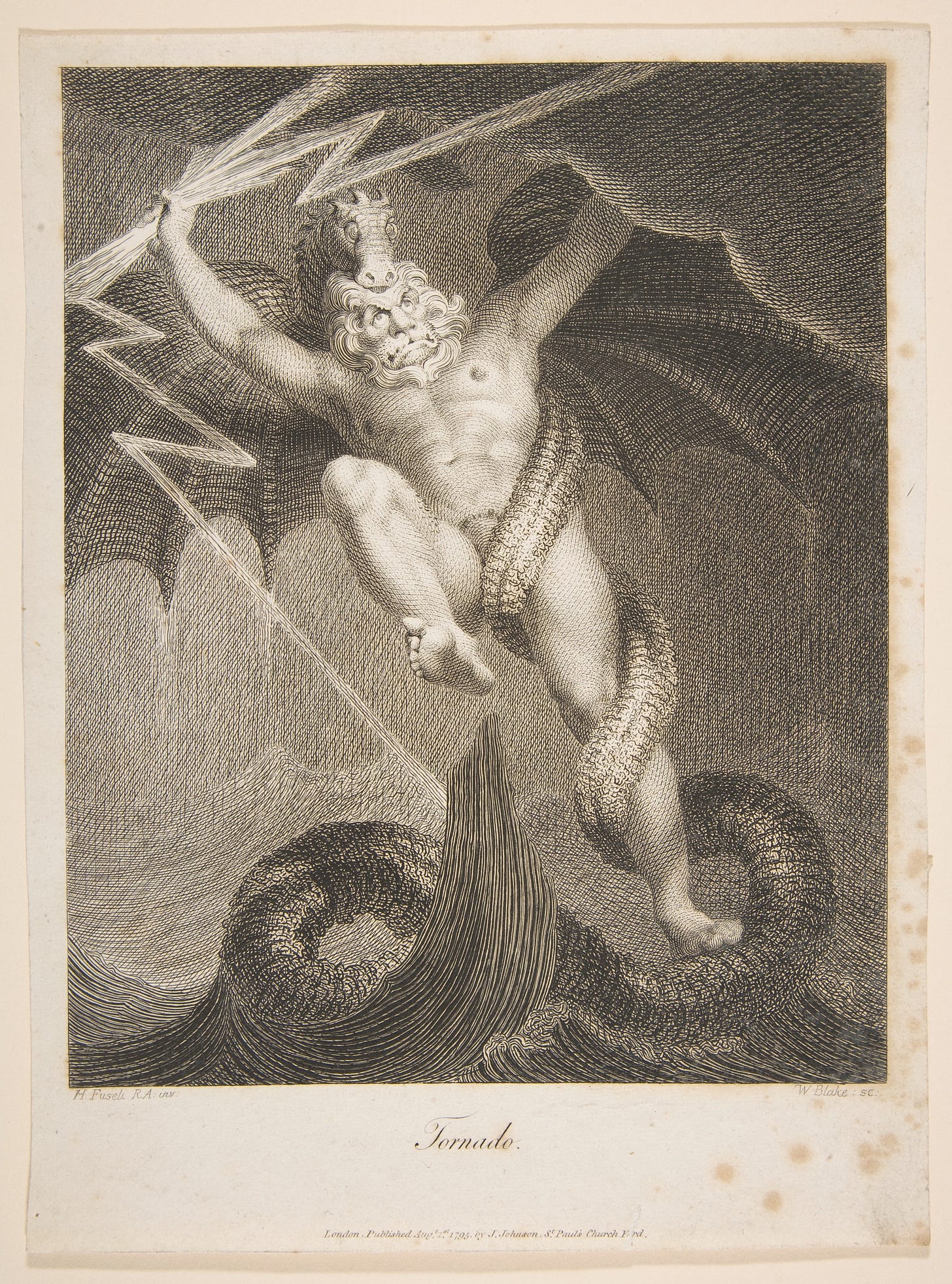

These gods share a number of similarities beyond the use of the thunderbolt as a terrifying weapon, such as an association with oak trees. Myths about them tend to involve a battle with a dragon or serpent: Zeus against Typhon (as in Blake’s illustration), Thor against the Ragnarök serpent Jörmungandr, Indra against the malevolent man-serpent demon known as Vitra or Ahi.3

Of course, divine or supernatural thunder also strikes in many non-Indo-European religions and mythologies. “The Lord’s voice is heard over the sea,” the Psalmist sings in Psalm 29. “The glorious god thunders; the lord thunders over the ocean.” In his apocalyptic vision, the Book of Revelation, John of Patmos sees and hears an angel who “cried out in a loud voice like the roar of a lion. And when he cried out, the seven thunders sounded their voices.”

In perhaps the most famous Japanese myth, the sun goddess Amaterasu is, depending on the teller of the tale, either so frightened or so enraged by her noisy younger brother, the storm god Susanoo, that she hides in a cave, causing an endless night.4 Susanoo himself, in the words of scholar Hirafuji Kikuko, is “a chaotic force, rampaging through the plain of high heaven and wreaking havoc among its divine inhabitants.” He is banished from heaven but redeems himself in a way that echoes his Indo-European counterparts:5 slaying the eight-headed serpent Yamata no Orochi and then pulling the legendary sword Kusanagi-no-Tsurugi out of its body.6

Japanese mythology includes another storm god known as Raijin, Raiden or Kaminari-sama. “He is most often depicted as a demonlike creature,” Barbra Teri Okada writes in a netsuke exhibition catalogue, “with a scowling face and clawlike hands and feet.”7 Norse mythology imagines thunder as Thor pounding his hammer; Japanese mythology images it as Raijin banging his drum. In some myths, Raijin is accompanied by a “thunder beast” called raiju, which would inspire the second-generation Pokémon Raikou.8

Thunder and lightning remain powerful signifiers of the supernatural in the fiction of a modern, post-mythological world. Macbeth begins with the stage directions “Thunder and lightning. Enter Three Witches;” thunder accompanies each of the witches’ subsequent appearances. “When shall we meet again,” asks the First Witch in the play’s first lines, “in thunder, lightning or in rain?”

“It was on a dreary night of November, that I beheld the accomplishment of my toils,” Victor Frankenstein recalls in Chapter V of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818). “I collected the instruments of life around me, that I might infuse a spark of being into the lifeless thing that lay at my feet.” Film adaptations of this scene, from James Whale to Mel Brooks, tend to represent this spark of being as a raging thunderstorm channeled through Frankenstein’s machinery.

These scenes reflect the reoccurring thunder and lightning imagery throughout the original novel, which evokes the myth of Prometheus stealing the fire of heaven from the thunder god Zeus. In Chapter VII, for instance, Frankenstein encounters his creation on a stormy Swiss night:

I perceived in the gloom a figure which stole from behind a clump of trees near me; I stood fixed, gazing intently: I could not be mistaken. A flash of lightning illuminated the object, and discovered its shape plainly to me; its gigantic stature, and the deformity of its aspect, more hideous than belongs to humanity, instantly informed me that it was the wretch, the filthy dæmon, to whom I had given life.

In the Star Wars universe, the use of force lightning is a telltale sign of a Sith, Emperor Palpatine’s signature means of torturing and killing his enemies (and allies, in the case of Darth Vader in Return of the Jedi.)

Macbeth, Frankenstein and Star Wars, the first three examples that occurred to me, only scratch the surface of the many, many magical or supernature characters associated with thunder and lightning; an exhaustive list would take up this entire post and then some.9

It would have to include Pikachu, whose arsenal of attacks includes ThunderShock, Thunder Wave, Thunderbolt and Thunder.10 “When several of these Pokémon gather,” the Red and Blue Pokédex warns its reader, “their electricity could build and cause lightning storms.”

As mentioned in a previous post on Spearow, Pikachu unleashes this power at one of the anime’s most dramatic moments: the desperate battle against a flock of wild Spearow, the moment where Ash wins Pikachu’s trust and their trainer-Pokémon partnership truly begins.

This returns us again to a quote from Pokémon co-creator Satoshi Tajiri, one that has informed this entire series: “the monsters are controllable by the players.”11 In the case of Pikachu, control of this particular monster means control of storms, of thunder and lightning: of a numinous natural phenomenon with mythical and even spiritual resonances. One would have to look far and wide for a more appealing, more archetypal power fantasy, especially for a young child.

Pikachu’s pika side, in other words, seems like a key ingredient of its worldwide fame. I’ll take a look at its chu side in two weeks.

Viridian Forest and the power plant.

Sheldon, J. S., and M. L. West. "The Wider Context: Common Elements in Indo-Iranian, Greek and Other Poetic Traditions and Mythologies." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol. 19, no. 4, 2009, pp. 509-528. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/wider-context-common-elements-indo-iranian-greek/docview/218935328/se-2, doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1356186309990083.

Miller, Robert D. "Tracking the Dragon Across the Ancient Near East." Archiv Orientalni, vol. 82, no. 2, 2014, pp. 225-III,409. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/tracking-dragon-across-ancient-near-east/docview/1629401850/se-2.

The other gods lure Amaterasu back out of the cave and she becomes the legendary ancestor of Japan’s imperial dynasty.

Are Pikachu’s regular battles against larger, dragon- or serpent-like creatures – Brock’s Onix, Jessie’s Ekans and Arbok, Blaine’s Rhydon in the anime; Brock’s Onix and Drake’s Dragonite in The Electric Tale of Pikachu; Brock’s Onix again, a Team Rocket gangster’s Rhydon, Giovanni’s Nidoqueen, Blue’s Charizard et al in Pokémon Adventures –distant, unconscious echoes of this archetypal battle between the thunder-wielder and the dragon?

According to traditional Shinto belief, this legendary sword still exists today as one of the Three Sacred Treasures used in the imperial enthronement ceremony. It is considered too sacred to be put on public display and is housed at the Atsuta Shrine in Nagoya.

Okada, Barbra Teri. Netsuke: Masterpieces from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art Publications, 1981.

Rai means ‘thunder’ in Japanese; a thunderstone evolves Pikachu into Raichu.

Furthermore, what haunted house would be complete without lightning flashing in its windows? Castle thunder became a cliché of Hollywood sound design for a reason.

And, in more recent games, Electro Ball, Spark and Discharge (via levelling up) as well as Volt Switch, Thunder Punch, Electric Terrain, Charge and Wild Charge (via TM.)

Larimer, Tim and Takashi Yokota. "The Ultimate Game Freak." Time, November 22, 1999.

I miss the design of Pikachu from the early days of the anime.

"How did this minor video game character become the most popular Pokémon, the face of the entire series?"

Well obviously, it's cause he's the cutest!

(said as sister of a former chinchilla owner)